Hatshepsut: The female king of Egypt

Hatshepsut: The female king of Egypt

Hatshepsut: The female king of Egypt

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Hatshepsut was born in 1507 BC, daughter of Thutmose I. When her father died, she married her half-brother, Thutmose II. Then Thutmose II died and she remarried: this time to her stepson, her husband’s son by another wife. The three-year-old boy became Thutmose III. He was clearly too young to rule, and so Hatshepsut ruled in his place as regent. Thus when Hatshepsut became pharaoh, she had the pedigree: daughter, sister and wife of a pharaoh.

At first, Hatshepsut took on titles befitting a queen, like God’s Wife, but by the time she had been ruling for seven years she took on the titles of a king. Monuments made in her honour depicted her in the attire of a king: crown, beard, crook and flail. Some have assumed this means Hatshepsut was a transvestite, but in fact these depictions of her were simply designed to portray her in her role as king, with the power that came with that title.

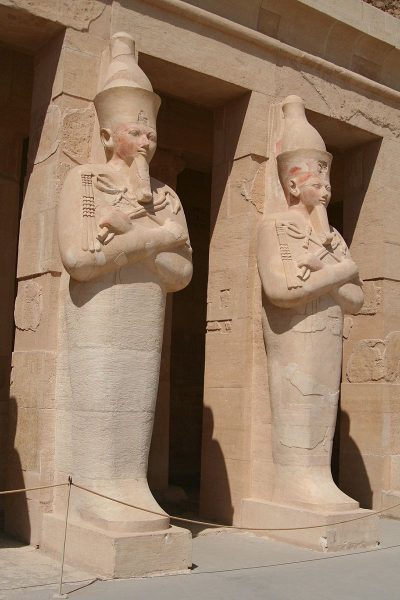

Statues depicting Hatshepsut as the male god Osiris

Was Hatshepsut a good king? It’s thought so. Her reign was a peaceful one. She established trade routes, and organised a trip to the Land of Punt. There, her delegation bought incense trees with the idea of planting them in Egypt to create a new natural resource. They also brought back ebony, ivory, gold, baboons and people to work as labourers.

Hatshepsut was very enthusiastic about building; indeed, she commissioned more builds than most other pharaohs, and they were grand, ambitious projects. She made many statues (today, most big museums in the world have at least one). She built monuments at the Temple of Karnak – one of a pair of obelisks still stands today, and it’s the tallest on the planet. She built temples, too, and the most impressive was her own mortuary temple.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut is at Deir el Bahri. The temple is very grand: it had pylons, a hypostyle, an avenue of sphinxes, a chapel and a sanctuary. It’s the closest Egypt came to classical architecture. So impressive is the temple that later pharaohs built their complexes nearby in an area now known as the Valley of the Kings.

But though they may have admired Hatshepsut’s building work, it seems not everyone admired the woman herself. Hatshepsut ruled until Thutmose III came of age at 18, and then she died in 1458 BC, whereupon she disappeared from records.

During the later reign of Thutmose III, attempts were made to scrub her from history, removing her image and cartouches from temples, and smashing and defacing her statues. The efforts were not thorough, however, and so many images of Hatshepsut remain. No one knows whether Thutmose III, or his son Amenhotep II, was behind this attempt to tarnish – or even eradicate – the memory of Hatshepsut, and whether the reason for this destruction was that she was a female king, possibly considered a dangerous precedent.

Statue of Hatshepsut with symbols of her power as a king removed: the beard, the Uraeus (cobra) and full crown

One thing is certain: with our understanding of Hatshepsut today, her legacy lives on as an empowering inspiration to women.

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Photo credits: 1) mareandmare/Shutterstock.com; 2) Steve F-E-Cameron, source; 3) Maxal Tamor/Shutterstock.com; 4) Francesco Gasparetti, source.

Wow that was so interesting Hannah.

Absolutely love the history lesson.

Thank you so much x

You’re most welcome! I enjoyed writing it.