An enduring trope: The damsel in distress

An enduring trope: The damsel in distress

An enduring trope: The damsel in distress

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

In recent years, the term ‘damsel in distress’ has come to have negative connotations, with an inference that the damsel in question is weak and in need of rescue by a man (often, the knight in shining armour). Heroines in movies and books are increasingly ‘anti-damsels’; much was made, for example, of Emma Watson’s ‘feminist’ interpretation of the role of Belle in Disney’s live-action Beauty and the Beast adaption.

Today, I want to unpick the assumption that the ‘damsel in distress’ is a theme that should be scorned and abandoned, and situate it where it has always belonged, at the heart of the romance genre.

Did you know that the demoiselle en détresse (from which our modern term derives) emerged as an archetype in medieval times, when it was noble and honourable for a man (a chivalrous knight) to protect a woman? Around the damsel character all kinds of folklore was created, from European fairy tales like Snow White and Sleeping Beauty, to romantic rescues in the Arabian Nights, to legends that continue to define to this day, such as that of George, patron saint of England, slaying the dragon to save a princess.

In these days, the damsel in distress was taken very seriously. Even in the nineteenth century, when melodramas were en vogue, the audience was enthralled: the poor heroine; would she be saved in time?

Then came the twentieth century, and an explosion of mediums through which to tell stories. The damsel in distress character endured across all kinds of genres, from soap operas to comic books. People flocked to see this moment on the big screen:

But a discomfort with the damsel in distress trope was emerging, for two reasons:

Women’s rights: Women don’t need rescuing by a man! cried impassioned females of the West. We can, and must, rescue ourselves.

Cynicism: All that is associated with emotionality and romance was dissonant in the prevailing mood of cynicism. How many people have scorned romance novels as fluffy, silly nonsense?

The result has been a schism in fantasy, whether in literature or on the stage/screen: on the one side, old-fashioned, romantic damsel in distress stories; on the other, stories in which the female character is astonishingly strong and independent (and perhaps rescues the male). Between the two extremes lie myriad attempts to navigate this treacherous territory, to balance what is honourable, romantic and realistic with what is idealised.

Why do I say ‘idealised’? Because the heroine who is never in distress is not real. ‘In distress’ in modern times is not restricted to being in mortal peril; it means exactly that: being distressed – hurting, in need. What relationship can be based on one party never being in need, never feeling pain and allowing the other to recognise, share and attempt to ease that pain? What heroine can truly never be in distress? Certainly not one a reader can empathise with and root for.

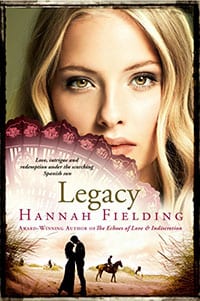

In my novel Legacy, the heroine, Luna, is a very strong, independent woman. She has travelled from her home in the United States for her work, fearlessly thrusting herself into a new, alien culture and engaging in the difficult task of secretly investigating her boss, Ruy. Luna would absolutely join the cry: Women don’t need rescuing by a man! We can, and must, rescue ourselves.

No, Luna does not need rescuing; she does not need Ruy. But when she is in distress – which invariably happens, because all stories of people include distress – she can choose to be helped by Ruy. She can, and she must, if she is to really connect with him.

Legacy: available to buy from my shop

Falling in love, giving your heart to another, requires naked, raw vulnerability, the exposure of your soul. It requires being that age-old damsel in distress and letting the knight gallop up and rescue you – and, crucially, it requires being his knight and rescuing him from his own distress; guiding him through his own pain. A damsel need not only be a damsel; she can be a knight too.

So, we have established that emotional distress is essential in the modern heroine. But what of the traditional physical rescue? Is there any place for that in modern stories? Take a look at this excerpt from Legacy:

He said nothing more, but trailed one warm finger down her cheek and gently turned her face towards him. ‘It’s all right now, querida. You’re safe now. I’m here and I’ll look after you. Come, let me take you home. You’re hurt and those cuts need to be seen to. I’ll sort out the car tomorrow.’

Luna pushed back her tears. She didn’t care about the cuts on her body, it was her aching heart she needed him to heal, futile as that seemed. As she tilted her chin up to him, she struggled to control the chaos of conflicting emotions he engendered in her.

‘Let’s get you to the car.’

Ignoring her small sound of protest, in one strong movement he scooped her up, one arm under her legs and the other around her shoulders, holding her tightly against him. Treacherous feelings flooded her. Oh, the warmth and tautness of his wonderful body! Despite her fatigue and confusion, Luna couldn’t help but enjoy those ephemeral few seconds of contact. His breath on the side of her face heated her cold, wet skin and her heart was pounding as she fought a compulsive urge to touch those generous chiselled lips, just inches from hers.

What do you think? I would love to hear your thoughts.