The ‘false’ doors of Ancient Egyptian tombs and temples

The ‘false’ doors of Ancient Egyptian tombs and temples

The ‘false’ doors of Ancient Egyptian tombs and temples

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The Ancient Egyptians had many beliefs about death and the afterlife, and their rituals and tombs and temples were carefully crafted in keeping with these beliefs. One core belief was that the ka part of the soul – the vital life force of the person – would leave the body after death but continue to exist.

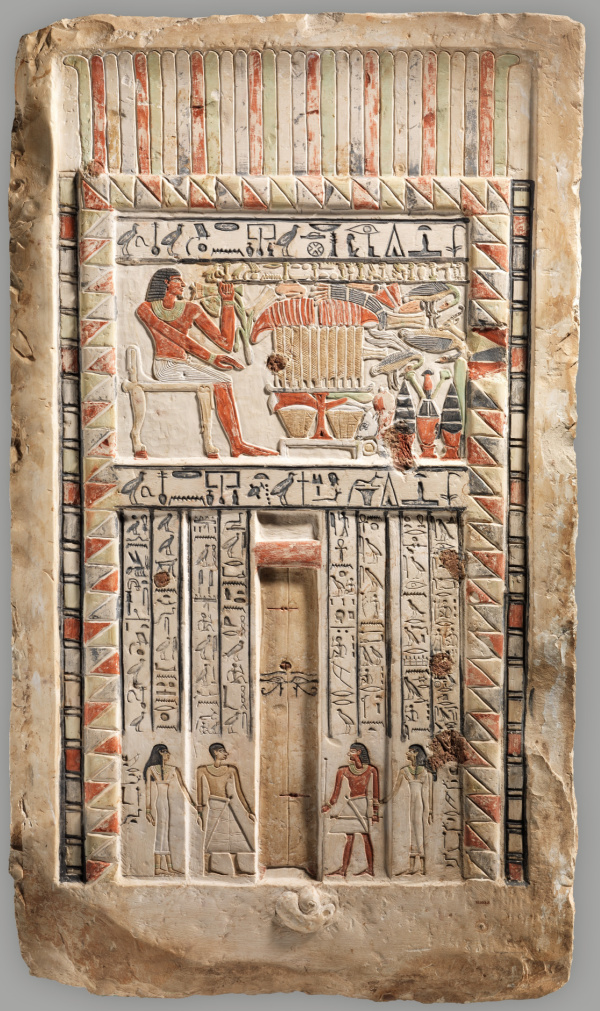

A ka door would be built in mortuary tombs and temples to create a threshold between the world of the living and that of the dead. This was not a real door, but a carving in the wall, and it represented an access point through which deities and the deceased could pass back and forth.

Typically, the door was situated on the west wall of the tomb or temple, because the Egyptians believed the land of the dead was to the west. It was on a slab before the door that people would leave offerings for the deceased, in the belief that the food and drink would sustain the ka.

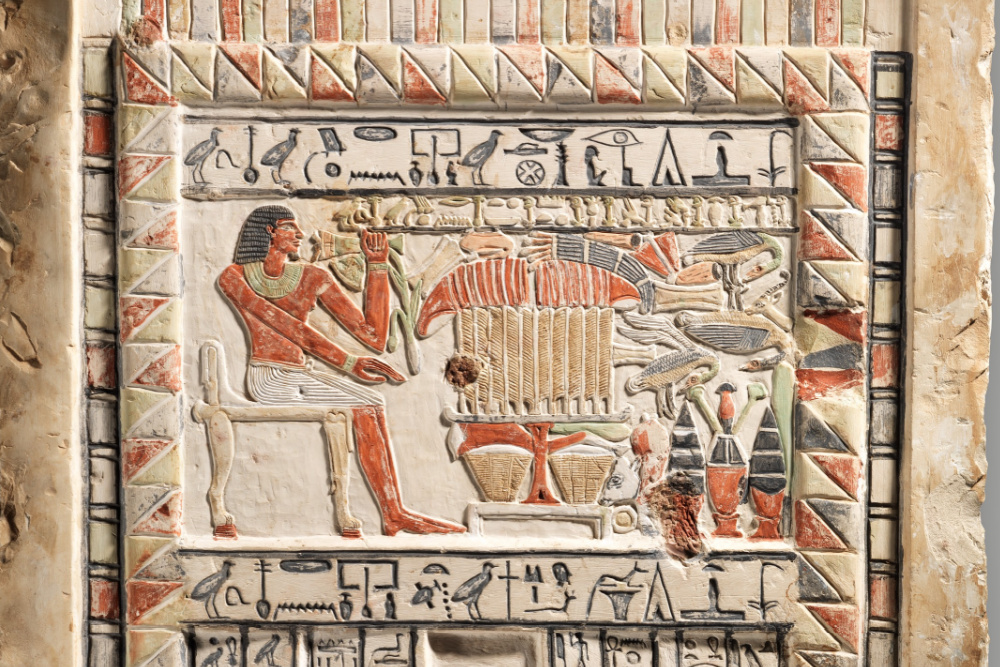

Pictured here is a false door from the Old Kingdom; it was found in the tomb of the royal sealer Neferiuca (c. 2150–2010 BC) in the Dendera area, and is on display at the Met Museum, New York. You can see Neferiuca at a table with his offerings.

Many false doors followed a similar design, inspired by the niched palace façade that was popular in architecture in the early Dynastic period, as seen in the pharaoh Djoser’s mortuary complex at Saqqara:

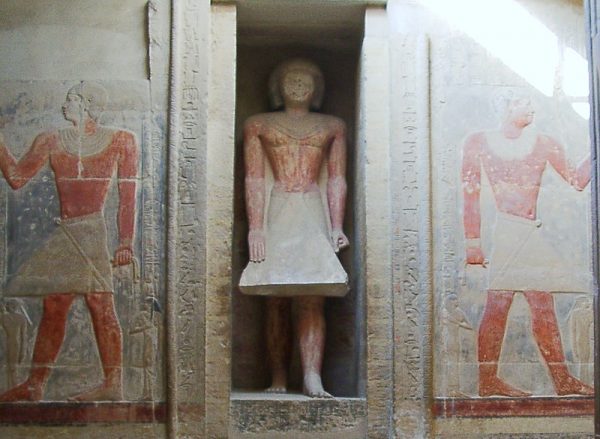

Some doors, however, differed in design, having as their focal point in the central niche a statue of the deceased. Here is the false door of the vizier Mereruka at Saqqara:

False doors were not only a means by which to connect with the dead; they also, it was believed, brought you closer to the gods. In temples devoted to the cult of a god, the false door sometimes backed onto a chapel, and worshippers believed that they could communicate through the door with the god. On the wall of the chapel were ‘ear stelae’ into which people would speak, believing their prayers would reach the ears of the god.

Stela of Mahuia, Memphis

By the time of the Eleventh Dynasty, false doors in tombs and temples had fallen out of favour. In the Middle Kingdom they continued to be represented in artwork on coffins, but over time beliefs and rituals evolved.

So, we are left with doors that lead nowhere. Or do they? I can imagine that the Ancient Egyptians found great comfort in the notion that a loved one, or a god, was just the other side of the door, listening. And who is to say that was, in fact, false?

Photo credits: 1) The Met; 2) Berthold Werner/Wikipedia; 3) HoremWeb/Wikipedia; 4) British Museum.