The immortality of writers

The immortality of writers

The immortality of writers

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Writers may see their craft as a means of self-expression, of creative exploration, or of sharing learnings and inspiring others. But how many of us writers see our labours as a way to secure eternal life?

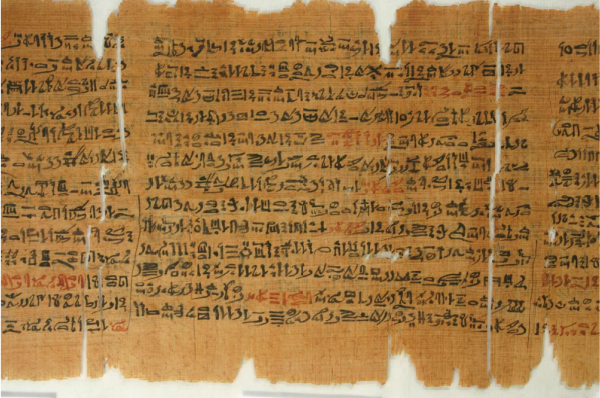

In the British Museum, London, there is a very, very old papyrus called The Immortality of Writers. It was found in Deir el-Medina, the village of the artisans who worked in the Valley of the Kings during the New Kingdom of Egypt, constructing and decorating the tombs. The artisans called their home Set Maat, ‘Place of Truth’, and it was the scribes’ job to capture truths in their writing.

Thanks to the degree of protection afforded by (at least initially) sealed tombs, some papyri placed there did not crumble to dust over the centuries but have at least in part survived to this day, much to the delight and wonder of Egyptologists. Among the papyri discovered at Deir el-Medina we have stories, songs, hymns, incantations and letters that give us a broad and fascinating picture of everyday life, culture and religion. The papyri also afford us a glimpse of the Ancient Egyptians’ philosophy.

Deir el-Medina

Of course we associate the classical civilisations, the Greeks and the Romans, with philosophy: the likes of Aristotle and Plato for the Greeks, and Marcus Aurelius and Cicero for the Romans. But they were not the world’s first deep thinkers by any means. The Egyptians wrote ‘wisdom texts’ in which their writers imparted important philosophical thoughts to the people; they were used for sebayt, meaning teachings or instructions.

The afterlife was a common theme in wisdom texts, as it was of great concern for people, and The Immortality of Writers is a text that promotes writing as means to ensure that you will live on long after your death. Dating from between the 19th and the 20th Dynasties (around the late 1100s BC), it is written from the perspective of a seasoned writer advising an apprentice, and it reads as follows:

If you would only accomplish this, becoming expert in writing:

Those writers of knowledge from the time of events after the gods,

those who foretold the future,

their names have become fixed for eternity,

though they are gone, they have completed their lifespan,

and all their kin are forgotten.They did not make for themselves a chapel of copper,

or a stela for it of iron from the sky.

They did not manage to leave heirs,

from their children, to pronounce their names,

but they have achieved heirs out of writings,

out of the teachings in those.They are given the book as ritual-priest,

The writing-board as loving-son.

Teachings are their chapels,

the writing-rush their child,

and the block of stone the wife.

From great to small, (all) are given as his children,

for the writer, he is their leader.The doors of their chapels are undone,

Their ka-priests have gone.

Their tombstones are smeared with mud,

their tombs are forgotten,

but their names are read out on their scrolls,

written when they were young.

Being remembered makes them, to the limits of eternity.Be a writer – put it in your heart,

and your name is created by the same.

Scrolls are more useful than tombstones,

than building a solid enclosure.

They act as chapels and chambers,

by the desire of the one pronouncing their name.

For sure there is most use in the cemetery

for a name in the mouths of men.A man is dead, his corpse is in the ground:

when all his family are laid in the earth,

It is writing that lets him be remembered,

in the mouth of the reciter of the formula.

Scrolls are more useful than a built house,

than chapels on the west,

they are more perfect than palace towers,

longer-lasting than a monument in a temple.Is there anyone here like Hordedef?

Is there another like Imhotep?

There is no family born for us like Neferty,

and Khety their leader.

Let me remind you of the name of Ptahemdjehuty

Khakheperraseneb.

Is there another like Ptahhotep?

Kaires too?Those who knew how to foretell the future,

What came from their mouths took place,

and may be found in (their) phrasing.

They are given the offspring of others

as heirs as if their (own) children.

They hid their powers from the whole land,

to be read in (their) teachings.

They are gone, their names might be forgotten,

but writing lets them be remembered.(source: University College London)

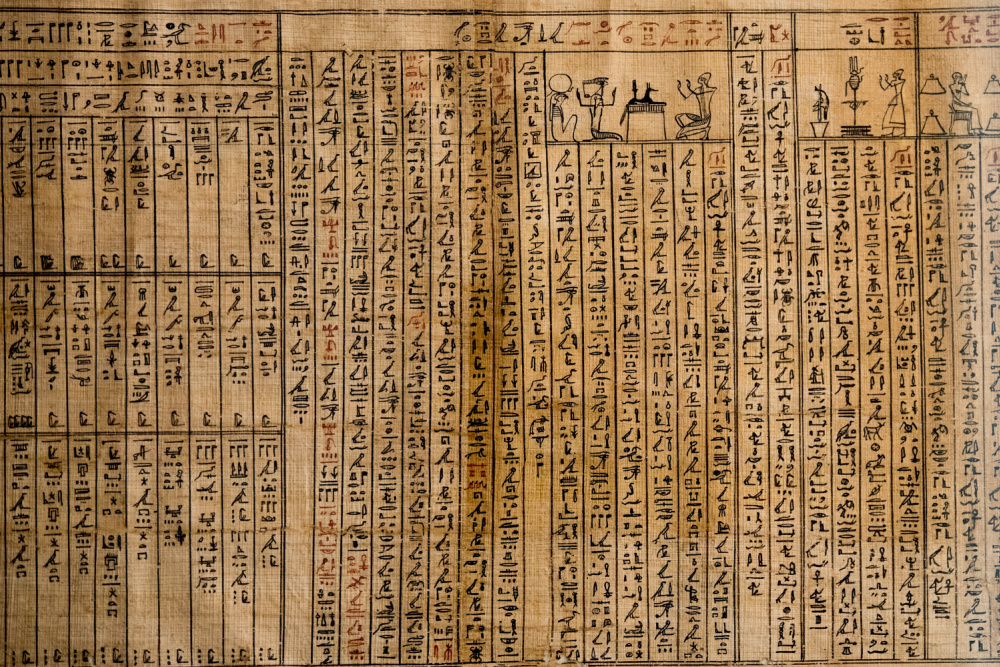

Part of the Chester Beatty IV papyrus, in which The Immortality of Writers is found

The Egyptians believed that speaking the name of a deceased person made them alive again; this was a key part of their beliefs about the afterlife. But what would happen when all of their family died too, when there was no one left to speak the name? Would they be forgotten, dead? Not, according to this text, if the person in question were a writer: ‘Their names have become fixed for eternity… writing lets them be remembered’.

It is a beautiful idea, don’t you think? I doubt many writers think in terms of their words enduring for eternity, but certainly legacy can be a reason for putting pen to paper – or, indeed, paintbrush to canvas, or fingers to piano keys.

It strikes me that no matter how much we advance as people, no matter how far technology takes us and how much activists transform society, we remain frightened of nothingness, not of death so much as ceasing to exist. Creative people can try to handle that fear by leaving pieces of themselves behind, by immortalising themselves through their art. For some, the remnants of their being after they pass away are few and small. For others, the body of work is revered, so that artists like Michelangelo and writers like Victor Hugo and composers like Beethoven and architects like Frank Lloyd Wright are known by many people.

Whatever your idea is of an afterlife, it is easy to imagine feeling peaceful at the knowledge your legacy lives on beyond your mortal body. As the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges said, ‘When writers die they become books, which is, after all, not too bad an incarnation.’

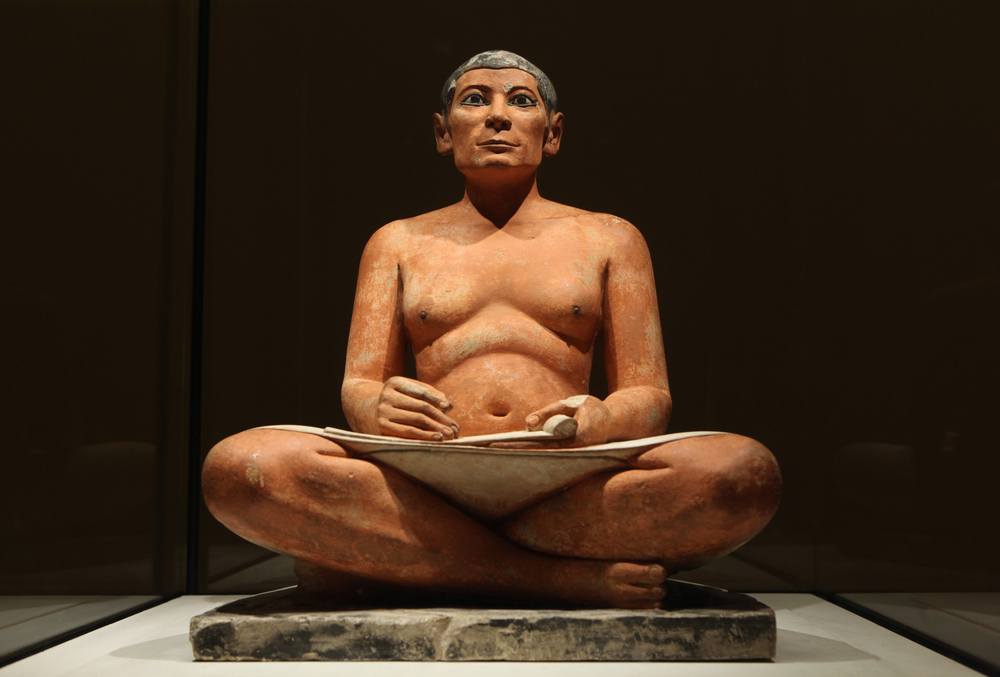

The Seated Scribe, c. 2500 BC, Louvre, Paris

Photo credits: 1) Andrea Izzotti/Shutterstock; 2) EvrenKalinbacak/Shutterstock; 3) British Museum; 4) Vladimir Wrangel/Shutterstock.