Three wonderful French writers

Three wonderful French writers

Three wonderful French writers

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

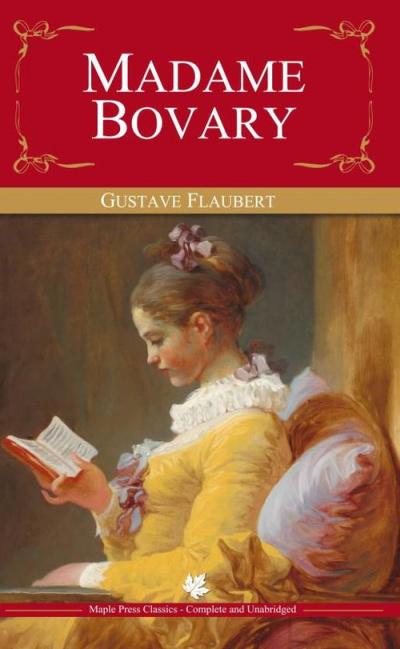

When I was approaching the end of my school education and the time came for me to decide what I would study at university, it was a very easy choice for me: French literature. I was an avid reader, a bibliophile and an aspiring writer, plus French was my first language, so the degree was a natural fit for me. But even more compelling was the fact that I had already fallen in love with books by some of France’s greatest writers; my copy of Madame Bovary, for example, was well thumbed.

It would take many blog posts – or an extraordinarily long one – for me to cover all of the French writers whose works I admire, and so in this article I am focusing on the three who have most moved and inspired me. Perhaps you’ll find an idea here for your next read.

Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880)

An infinity of passion can be contained in one minute, like a crowd in a small space. – Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

Gustave Flaubert, c. 1865

Gustave Flaubert lived most of his life in a small hamlet in Normandy. As a young man he studied law in Paris, but the city life was not for him. His first novel, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, was about an Egyptian monk. When he showed the first draft to two writer friends, their response was to tell him to discard the book and start again, and this time to write about real life, not fantasy. It turned out to be good advice: over the next five years Flaubert found his stride in literary realism as he wrote the novel for which he is now best known, Madame Bovary.

Love, that marvellous thing which had hitherto been like a great rosy-plumaged bird soaring in the splendours of poetic skies, was at last within her grasp. – Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

The story centres on the beautiful and charming Emma Bovary, who dreams of being like the heroine in the novels she reads. Instead, though, she is stuck (so she sees it) living the life of a doctor’s wife in a dull provincial setting. In search of a better life – one characterised by passion and luxury and beauty – she takes a path that leads to debt, adultery and eventually, tragically, her own ruin.

Madame Bovary caused quite the stir when it was first published, in 1856, so much so that Flaubert was put on trial for immorality. He was acquitted, thankfully, and the book became a bestseller, not simply for its story but for Flaubert’s astonishing skill as a writer. He was always seeking le mot juste (the right word), determined to express his meaning elegantly and precisely. He was a deeply thoughtful and insightful writer, and he has been a great inspiration to me in my own writing.

The art of writing is the art of discovering what you believe. – Gustave Flaubert

Victor Hugo (1802–1885)

He never went out without a book under his arm, and he often came back with two. – Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

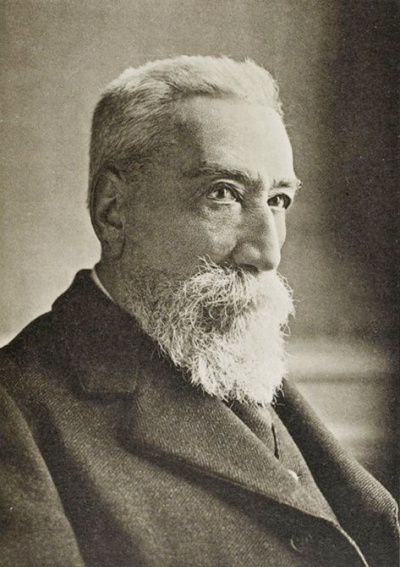

Victor Hugo, c. 1870

Victor Hugo was a hugely prolific and hugely influential writer in 19th-century France, and was a major figure in French Romanticism. Through his writing, he sought to bring about change; he had strong views on the state of his country and was not afraid to share them! Like Charles Dickens writing in England, Hugo used the medium of the novel to deliver important commentary on social injustice. Here is how Hugo introduced his 1862 novel Les Misérables:

So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age – the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of women by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night – are not solved… so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.

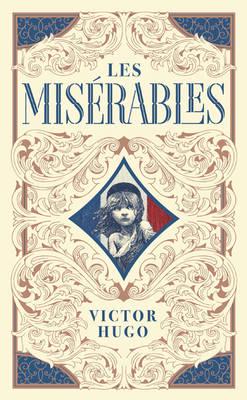

Les Misérables explores the underworld of Paris through the story of Jean Valjean, a man made a convict when he was caught stealing a loaf of bread. It’s a story of love and redemption, morality and justice.

To love another person is to see the face of God. – Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

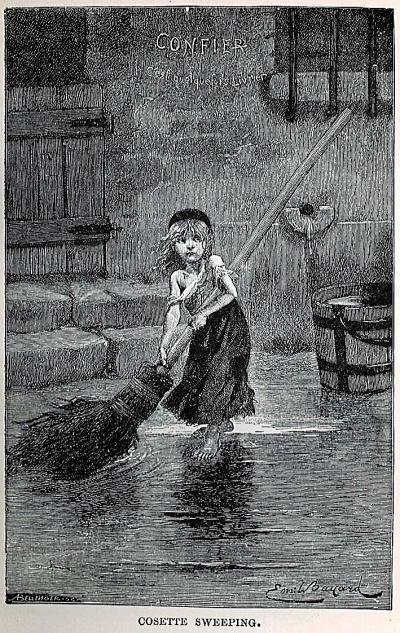

The original artwork of the orphan Cosette is to this day an iconic image, featuring often in cover art for the book.

Illustration by Émile Bayard (1862)

Barnes & Noble collector’s edition, 2017

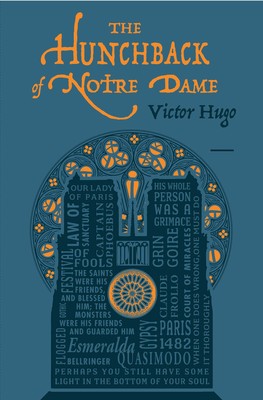

Les Misérables is famously a long novel (split into five volumes). A more manageable Victor Hugo book is his equally famous The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831). The novel was in fact published as Notre-Dame de Paris, so-named for the famous Parisian cathedral where the story takes place. It’s the tragic story of Esmeralda, a beautiful young Romani dancer, and Quasimodo, the bell ringer of the cathedral.

Love is like a tree: it grows by itself, roots itself deeply in our being and continues to flourish over a heart in ruin. The inexplicable fact is that the blinder it is, the more tenacious it is. It is never stronger than when it is completely unreasonable. – Victor Hugo, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame always reminds me of another classic French novel, that of The Phantom of the Opera (1910). Gaston Leroux’s spooky story, about a love triangle between a young woman, a young man and a ‘phantom’, is set in the Palais Garnier, an actual opera house in Paris, and while it is fiction, it incorporates a good deal of fact. Fascinating if you’re interested in Paris, its history and its architecture.

If I am the phantom, it is because man’s hatred has made me so. If I am to be saved it is because your love redeems me. – Gaston Leroux, The Phantom of the Opera

Anatole France (1844–1924)

In art as in love, instinct is enough. – Anatole France

Anatole France, c. 1921

Anatole France was indisputably a great writer, as evidenced by his being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921. The Prize judges honoured his ‘nobility of style’, ‘profound human sympathy’, ‘grace’ and ‘true Gallic temperament’.

Anatole spent his life surrounded by literature: his father owned a book shop, and during his career Anatole worked as a cataloguer and eventually a librarian for the French Senate. His works range from poems, plays and novels to literary and social criticism. Like Victor Hugo, he ruffled feathers with his unapologetic writing, and the year after he won the Nobel Prize, the Catholic Church added all of his works to their list of banned publications.

I incorporated one of my favourite Anatole France quotations into my first novel, Burning Embers:

We chase dreams and embrace shadows.

France was such an insightful writer, and I have a kept in a notebook my favourite quotations from his works, including:

All changes, even the most longed for, have their melancholy; for what we leave behind us is part of ourselves; we must die to one life before we can enter another.

–

It is human nature to think wisely and act in an absurd fashion.

–

To accomplish great things, we must not only act but also dream, not only plan but also believe.

–

If we don’t change, we don’t grow. If we don’t grow, we aren’t really living.

I will leave you with one that always makes me chuckle:

Never lend books, for no one ever returns them; the only books I have in my library are books that other folks have lent me.

Far better to gift a book you love, and keep a copy for yourself!

Picture credits: pictures of Flaubert, Hugo and France; Émile Bayard illustration: public domain, via Wikipedia. Book cover art: Maple Press, Barnes & Noble, Canterbury Classics.