The era of Indiscretion: 1950s Spain

The era of Indiscretion: 1950s Spain

The era of Indiscretion: 1950s Spain

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Readers of my new novel Indiscretion will find themselves transported not only to a beautiful location – the ancient cities and wild landscapes of Andalusia, Spain – but also to another time.

Readers of my new novel Indiscretion will find themselves transported not only to a beautiful location – the ancient cities and wild landscapes of Andalusia, Spain – but also to another time.

What do you expect of a novel set at the beginning of the 1950s? This was a decade in which many Western countries saw widespread changes. The Second World War had changed societies forever, and the transformations that had begun gathered pace in the post-war years. Every element of lifewas in flux. Many women, for example, had worked during the war, while the men were at the front, and were now unwilling to relinquish their newfound independence and freedoms. The scene was set for a movement that would culminate, in the 1960s, with major civil reforms and an entirely new way of living that forms the basis of how we live today in countries like France and the UK and the US.

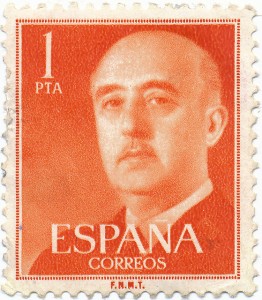

But what about Spain? In the era in which Indiscretion is set, you may expect Spain to have been keeping pace with other countries. It was not. After a long civil war, General Franco had claimed victory. His policy was one of authoritarianism and isolationism. He was not, unlike leaders of contemporary countries, looking to build Spain into a modern, forward-thinking nation that bestowed rights and liberties on its citizens. His ‘New Spain’ was a place locked into the old ways; a visit to some parts of Spain, like the area of Andalusia in which my story is set, was like stepping back in time. Take, for example, Alexandra’s first glimpse of Spain:

The hundred-year-old steam locomotive lurched through a parched yellow and brown countryside on worn-out tracks, winding north along Andalucia’s rocky coast. The train was crowded, but amazingly, at every stop, more people managed to force themselves in, driving into even closer intimacy those who were already packed in. Spaniards, Alexandra noticed, seemed to journey with an obligatory stock of food, and that of the passengers was now roped on the luggage racks above their seats. At the last station, a huge barrel of a man had boarded the train with a basket, from which protruded the head of a protesting goose.

Further on:

The carriages of the train had been stuffed to bursting with baskets of clucking hens, men whistling and shouting to each other, women with luggage and paraphernalia piled high against the windows, and even the odd goat or two.

The train had high-backed wooden benches, the seating arranged in cubicles on either side of a gangway. Some of the windows were broken, and people climbed through them to grab a seat. A chattering, shouting medley of voices had filled the carriage – there was none of the usual reserved and dignified behaviour Alexandra had read about in the books about the Spanish that she’d picked up at her local library. The strange smells of food, sweat and livestock permeated the atmosphere.

The train is old, with broken windows, and the tracks are worn out. The carriage is very overcrowded, and the people aren’t what Alexandra is used to back home, in London: they clamber in windows, they squeeze in too close, they’re rowdy, they carry livestock.

This is Franco’s New Spain, which her Aunt Geraldine tried to warn her off. It was madness, Aunt Geraldine said, for a woman to travel unchaperoned in such a conservative country,not to mention one still broken and impoverished by civil war. Unchaperoned? It seems like such an old-fashioned word, doesn’t it, in a 1950s-set novel. But it is apt. Alexandra, who in London was an independent young woman who enjoyed plenty of freedom, has stepped into a very different society in which she faces old-fashioned prejudices and expectations.

And when you are trying to make a life for yourself in a society that is so quashing of your natural desires and spirit, avoiding any kind of indiscretion becomes very difficult indeed…