‘In Spain blood boils without fire’: The power of the proverb

‘In Spain blood boils without fire’: The power of the proverb

‘In Spain blood boils without fire’: The power of the proverb

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Followers of my Twitter account (@FieldingHannah) will know that I love proverbs: simple sayings that contain stark truth and wisdom. For each of my novels, I research proverbs that are particular to the setting, and for Indiscretion, that meant a fascinating exploration of the many and varied Spanish proverbs.

I wanted to look beyond translations of commonly known English proverbs, and root out those with a true Spanish flavour. I found that the origins of many Spanish proverbs date back to Babylon, and came to Spain via Greece and Rome and North Africa. The first anthology of Spanish proverbs, Proverbios que dicen las viejas tras el fuego, dates back to the 15th century, and this was beyond the scope of my reading; but the 17th-century Don Quixote by Cervantes provided rich fodder. The character Sancho Panza can barely utter a sentence without bringing in a proverb, so much so that he drives Don Quixote to distraction:

‘God and all his saints curse you, wretched Sancho,’ said Don Quixote, ‘as I have said so often, will the day ever some when I see you speak an ordinary coherent sentence without any proverbs? Senores, your highness should leave this fool alone, for he will grind your souls not between two but two thousand proverbs brought in as opportunely and appropriately as the health God gives him, or me if I wanted to listen to them.’

Well, of course I endeavour not to go the way of Sancho Panza and weigh down my narrative with 2,000 proverbs! Instead, I weave them into the story. For example, Agustina, Alexandra’s duenna, tells her:

‘Deja el jabalí dormir, es solo un gran cerdo, molestalo y estas muerto, Let the boar sleep and he’s just a large pig, upset him and you’re dead. It’s the same with the gitanos. Leave them alone and the damage is small: a bit of poaching and petty thieving. Attack them, try to pick a quarrel, and you open the gates to a flood of troubles.’

A proverb is an ideal way to convey a warning, adding gravitas to the words. But it can also be a way to colour words; to convey a mood. Here, Alexandra’s grandmother is ostensibly backing off and leaving Alexandra to make her own decisions, but the tone of the proverb she selects makes clear her true feelings:

The Duquesa looked at her granddaughter wearily; the severity in her eyes had given way to an expression of anxious affection. She sighed. ‘You’re right, I can’t stop you from seeing whomsoever you choose. You are indeed old enough to make up your own mind and take what decisions you think best. At the end of the day, we all have to make our own mistakes do we not? As the proverb goes: Treinta monjes y su abad no pueden hacer un rebuzno de burro en contra de su voluntad, thirty monks and their abbot can’t make a donkey bray against his will.’

How delightful to be compared to a donkey! There is a decided edge to the duquesa’s words. But I also love to use proverbs without any suggestion of hidden meaning, simply as a means of authentic expression of a feeling, as here:

Salvador himself walked with the air of someone who’d decided to take a holiday from a usually stressed life. For once, he seemed relaxed, almost carefree. ‘Que bonito es hacer nada, y leugo descansar, How beautiful it is to do nothing, and then rest afterwards – as the proverb goes. That phrase could have been coined specially for the Sevillians, I think.’ He turned to her, his eyes alight with a twinkling expression she’d not seen in them before.

The proverb simultaneously reveals Salvador’s mood and his identity as a proud Spaniard. He has taken it upon himself to educate Alexandra about his home, and the proverb is one of the ways he tells her about himself and his people.

That is the true power of the proverb: to convey history and culture and philosophy in just a few words. That is why I chose the following proverb for the epigraph of Indiscretion:

En la sangre hierve España sin fuego. In Spain blood boils without fire.

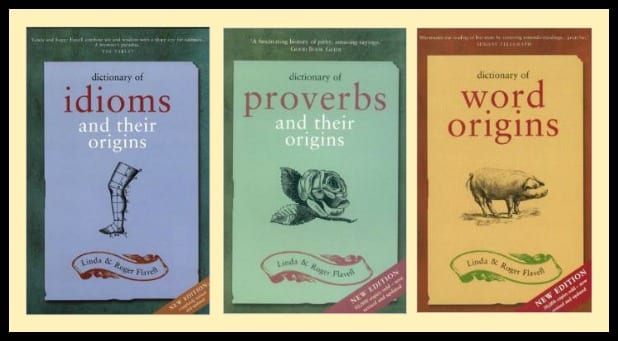

If, like me, you are fascinated not only by proverbs but by their origins, I can recommend the Dictionary of Proverbs and Their Origins by Linda and Roger Flavell, along with the accompanying books in the series: