Spanish art #1: Salvador Dalí

Spanish art #1: Salvador Dalí

Spanish art #1: Salvador Dalí

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Art features prominently in my new novel, Masquerade. The heroine, Luz, is a writer, and she has been commissioned to write a biography of artist Count Eduardo Raphael Ruiz de Salazar, by his nephew, Andres de Calderón. Securing the job requires Luz to have a great deal of knowledge of the modern art world, and I confess this was a part of the book very close to my heart which I thoroughly enjoyed writing!

Salazar was one of the great painters of modern Spain, influenced by Surrealists like Magritte, Dalí, Ernst and Miró; by the colours of Fauvism; by the old masters, especially Velázquez and Caravaggio for their dramatic realism; and by the graphic artist Escher. He is a fictional character, the product of my imagination, but feels quite real to me, because his influences are very much of reality.

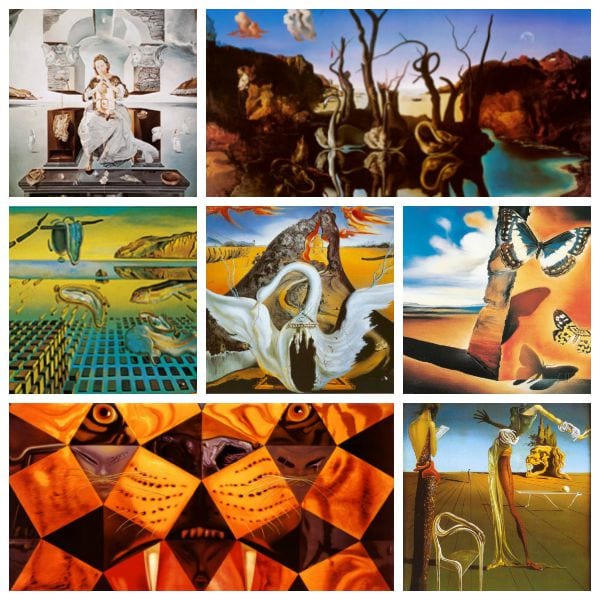

In a ‘Spanish art’ series of blogs, I will look at those inspirations – the most influential artists of Spain. Today, I begin with one of the most famous artists, Salvador Dalí, and look at why his style of painting has resonance in my novel Masquerade.

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marqués de Dalí de Pubol was born in 1904 in Catalonia, and would claim his ancestry was Moorish. He was named for his older brother, who had died the year before Dalí’s birth, and was told he was his reincarnation – which greatly influenced his sense of identity. He would later say that his brother ‘was probably a first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute’.

When Dalí was sixteen, his mother died. He said of this tragedy: ‘I could not resign myself to the loss of a being on whom I counted to make invisible the unavoidable blemishes of my soul.’ At eighteen, he moved to Madrid to study at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. That opened the door to developing his painting style, influenced heavily by study of Renaissance masters’ works, and brought him into contact with various notable artists of the time, including Miró and Picasso.

He experimented with various styles and forms. Two of his design works are the most iconic of the Surrealist movement: the lobster telephone (1936) and May West’s lips sofa (1937).

Painting was a central focus; he produced more than 1,500 paintings in the course of his career. He was unafraid of mixing influences and styles, to the bemusement of critics and delight of aficionados. He joined the Surrealist group in Montparnasse quarter, Paris, but was later ejected for being too fond of fame and fortune and for increasingly commercialising his work (did you know he designed the Chupa Chups lollipop logo?). Many condemned him for undertaking publicity stunts to market his work, but in more recent years some art historians have redefined some of his antics as performance art.

He developed an eccentric mien, outlook and appearance, with a quirky dress sense and moustache. Over the years his eccentricity and grandiose behaviour made him as famous as his art. Bizarre behaviour included delivering a lecture in a deep-sea diving suit; making public appearances with an anteater in tow; speaking a hybrid mix of English, Spanish, Catalan and French; doing book signings from a bed while hooked up to a heart monitor; and refusing to pay for meals but instead drawing on the tabs (quite rightly, he reasoned that his art on these scraps of paper would be worth much more than cash paid for the food). ‘Some say he’s a showman who prostitutes his art, others that he simply lives his brand of Surrealism,’ I write in Masquerade. Certainly, Dalí’s behaviour came to overshadow his art at times, which was a source of conflict for those who admired his work.

Initially in his adulthood he identified with anarchism and Communism. But he did not hold true to those ideals. Unlike many Spanish artists, Dalí accepted Franco’s dictatorship, which angered many of his peers. He even went so far as to support it at times, sending congratulatory telegrams for actions Franco took. He did not take part in the Spanish Civil War or the Second World War, for which he was heavily criticised; George Orwell called him ‘a disgusting human being’ for not supporting France, which had supported his art.

He married a lady named Gala, whom he cast as his muse and who was tolerant of Dalí’s infidelity with others, and they made a home at Port Lligat, on the coast near Cadaqués. He survived her by a few years, but was broken by her death, and he followed her at the age of 84. He was interred in a crypt beneath the stage in his biggest work of art: the Dalí Theatre and Museum in his hometown, Figueres. He said of his resting place and memorial:

‘I want my museum to be a single block, a labyrinth, a great surrealist object. It will be totally theatrical museum. The people who come to see it will leave with the sensation of having had a theatrical dream.’

‘A theatrical dream’… those words resonated with me as I wrote Masquerade. As Andrés tells Luz in the novel:

‘André Breton, who, as you know, was the father of Surrealism said, “The imaginary is what tends to become real.”’ He gave a wry smile. ‘The boundary between illusion and reality is a fictitious one.’

What is real, and what is masquerade? What can be trusted, and what is illusion? More importantly: does the distinction matter? Dalí said, ‘Surrealism is destructive, but it destroys only what it considers to be shackles limiting our vision.’ Can Luz and Andrés navigate a surreal world, and what reality will they discover?

I will leave you with a quotation from Dalí that says everything about his influence on me and so many others: ‘A true artist is not one who is inspired, but one who inspires others.’