Divided by a common language: British and American book editions

Divided by a common language: British and American book editions

Divided by a common language: British and American book editions

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

George Bernard Shaw said, ‘The British and the Americans are two peoples divided by a common language.’ I have always been intrigued by this quotation, and the truth behind it, especially when it comes to book publication.

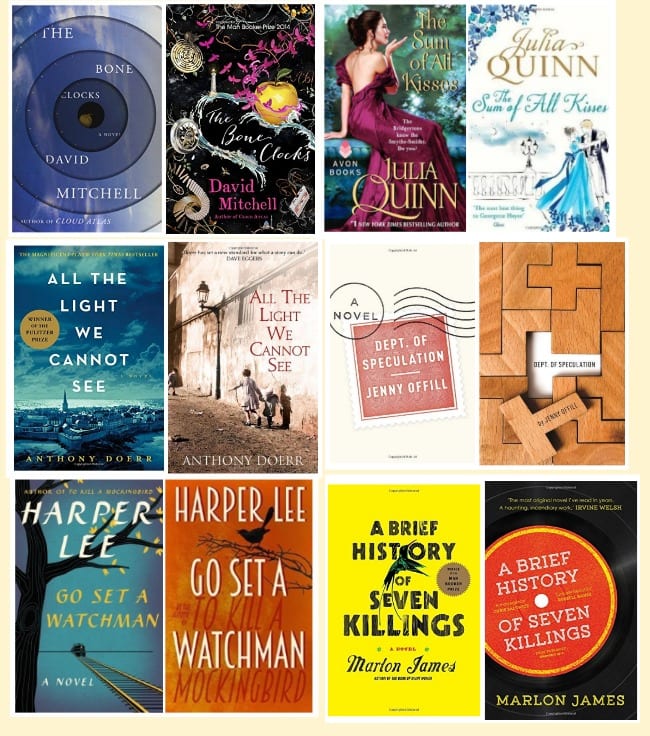

No doubt you are aware that British and American editions of the same book frequently have different cover art. Here are some examples:

You probably also know that a British edition and an American edition of a book differ in terms of the text itself: British and American English are stylistically different.

You probably also know that a British edition and an American edition of a book differ in terms of the text itself: British and American English are stylistically different.

Many changes are to spelling, punctuation and grammar changes; for example, changing ‘color’ to ‘colour’, shifting the placement of a closing quote mark and pulling back from pluperfect tense usage.

Others differences, however, come down to terminology – which can rile readers. For example, while Harry Potter fans largely accept changes like ‘car park’ to ‘parking lot’ and ‘jumper’ to ‘sweater’, many disagree strongly with the US publisher Scholastic’s editorial decision to change the title of the first book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, arguing that it belittles Americans who are quite capable of understanding the original term ‘philosopher’.

On the subject of book titles, these can also differ. Did you know that Diana Gabaldon’s successful novel Outlander was published in the UK with the title Cross Stitch? That Where’s Waldo becomes Where’s Wally in Britain? Here are some more notable examples:

* Cecelia Ahern: Love Rosie (US), Where Rainbows End (UK)

* Agatha Christie: What Mrs. MacGillicuddy Saw! (US), 4.50 from Paddington (UK)

* Lucy Maud Montgomery: Anne of Windy Poplars (US), Anne of Windy Willows (UK)

* Louisa M. Alcott: Little Women, Part II (US), Good Wives (UK)

* Philip Pullman: The Golden Compass (US), Northern Lights (UK)

Like it or not, variant editions on either side of the pond are accepted by most readers as necessary, given the differences in the two forms of English. But what of differences in editions that are nothing to do with the British and American English? In that case there is potential for readers to become quite hot under the collar.

Recently, a professor from Birkbeck, University of London, published a paper entitled ‘“You have to keep track of your changes”: The Version Variants and Publishing History of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas’. Dr Martin Paul Eve, Professor of Literature, Technology and Publishing, was examining David Mitchell’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel using both a UK paperback version and a (US) Kindle version when he happened to notice striking differences between the two editions that went far beyond simple British/American language translation.

The differences are widespread; the paper includes some thirty pages of examples. The Guardian cites the following one:

From the UK text: “Historians still unborn will appreciate your cooperation in the future, Sonmi ~451. We archivists thank you in the present. […] Once we’re finished, the orison will be archived at the Ministry of Testaments. […] Your version of the truth is what matters.”

From the US text: “On behalf of my ministry, thank you for agreeing to this final interview. Please remember, this isn’t an interrogation, or a trial. Your version of the truth is the only one that matters.”

I confess I was quite shocked when I read these two extracts. They are so markedly different that it seems impossible that both would be simultaneously published as the same work.

In the abstract to his paper, Dr Eve explains how the differences came about:

In 2003, David Mitchell’s editorial contact at the US branch of Random House moved from the publisher, leaving the American edition of Cloud Atlas (2004) without an editor for approximately three months. Meanwhile, the UK edition of the manuscript was undergoing a series of editorial changes and rewrites that were never synchronised back into the US edition of the text. When the process was resumed at Random House under the editorial guidance of David Ebershoff, changes from New York were likewise not imported back into the UK edition.

It is difficult, therefore, to settle on which is the ‘definitive’ book – and the issue arises of which book award panellists and educators (the novel is widely taught and studied) are reading.

Have you read Cloud Atlas? Is so, how do you feel knowing that what you have read differs to what others have read? If not, would you read the book now – and which version? Do you think it is important that a definitive work exists? That books are only ever ‘translated’ and not significantly edited and rewritten in new editions? I would be interested to hear your thoughts.

Sometimes when I read a book, I can tell the difference between an American writer and British, not always the spelling differences but the style as well. In saying that, the majority of the books I read are by British writers (unless it’s a treasure hunt type book, then it’s usually an American author) funny I have only just realised this after I have read your post and went to have a look at my books!

I have just received the hardcover edition of Masquerade yesterday, I can’t wait to start it!

Thank you, Michelle. It’s really interesting that you can tell the difference in the style. In another life I’d love to study that for a PhD!

I have been thinking about this all day! It’s not some much a visible difference, but more of a feeling when I read. It’s a bit hard to describe but you may know what I mean? It does depend on the era that the book is written as well.

I think I know what you mean. I studied French literature at university and I think French novels have their own ‘feel’ as well.

http://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/53684e74b852afaa7aee3e52bc298f7c943167c770e83a4383f30e5508daf197.jpg

Seeing the link to this discussion I thought of the quote, Two countries separated by one language.