Categorising romance novels

Categorising romance novels

Categorising romance novels

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Many years ago, when I set pen to paper and wrote the first draft of what would become my debut novel, Burning Embers, I thought a lot about the setting and the story and the characters and the mood – and I thought very little about specific categorisation for the book I was writing. Genre was important in the sense that I knew I was writing romance, but I didn’t drill down further and consider what type of romance I was creating; I simply wrote the book.

Fast-forward to the start of this decade, and I discovered, when I came to submit the manuscript to publishers, a whole world of categorisation of which I had been largely unaware. What kind of romance was Burning Embers? publishers wanted to know. It was easy to determine what the novel was not: fantasy or paranormal, for example. But other categorisations required consideration. Burning Embers is set in the 1970s; did that make it historical fiction or contemporary? It contains some descriptions of intimate moments; did that make it erotic?

I recall, back when I was filling in publisher forms, thinking that it would have been far easier had my book fit very neatly into one (and only one) category; that perhaps if my novel did so, my chances of securing a publishing a contract would be greatly improved.

Yet I knew this fundamental truth of writing: you must write the book that wants to be written. Not a book you think a publisher/agent/reader wants; a book that comes from you, from your soul – from the muse. As one of the most respected and influential writers of the 20th century, Franz Kafka, put it:

‘Don’t bend; don’t water it down; don’t try to make it logical; don’t edit your own soul according to the fashion. Rather, follow your most intense obsessions mercilessly.’

Thus writers will always write books without much thought for categorisation. Why, then, need categorisation exist? The general idea is that categorising books into genres, and sub-genres, and sub-sub-genres, is helpful to booksellers, in presenting their wares for sale; and to readers, in browsing for books that fit their preferences. And yet it seems the difficulty of classification spills over to this end of the process as well.

Recently, I read with interest an article entitled ‘A Look Inside America’s First Romance and Erotica-Only Bookstore’, exploring the Ripped Bodice bookshop in LA, which is run by two romance-novel-loving sisters, Bea and Leah. Given that the store specialises in romance novels, organisation of novels is by sub-genre. The main ones are historical, contemporary, paranormal and erotica, along with ‘islands of other specialty sub-genres like LGBTQ, suspense, cowboys…’. But categorisation can lead to confusion, as Leah explained:

‘How do you shelve a book that’s lesbian vampire erotica? Does it go in the lesbian section, the vampire section, or the erotica section? These are real questions we find ourselves asking.’

Interestingly, Leah suggests that ‘the nature of… digital marketplaces makes categorization there intrinsically easier than for a brick-and-mortar shop’. Certainly, I have found through working closely with my publisher, London Wall, that the many categories on the websites of retailers like Amazon allow for all manner of different ways to categorise a book. At the time of writing, for example, my Andalucían Nights series is categorised as follows on Amazon.com:

Indiscretion (Book 1): Books > Romance > Historical > 20th Century

Masquerade (Book 2): Books > Romance > Multicultural

Legacy (Book 3): Books > Romance > Contemporary

I am not sure, however, that the wide range of categories that can be applied to books is always helpful to the reader, because often one category alone does not adequately express the essence of a book. Taking a look at Amazon.com’s sub-categories for romance (which, incidentally, differ from the Amazon.co.uk list), I could argue that the books of my Andalucían Nights series could fit into these categories: Multicultural, Heroes/Rich & Wealthy, Themes/Beaches, Themes/International, Themes/Love Triangle, and Themes/Workplace.

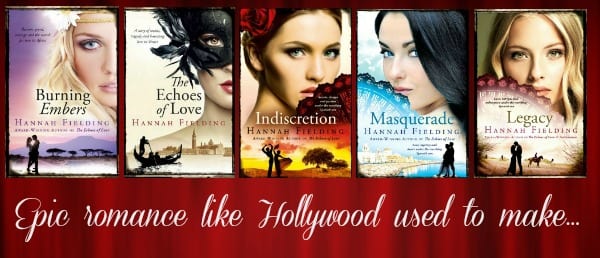

Ultimately, I am happy for my fiction be categorised in any genre that sensibly fits my writing. The Echoes of Love and Burning Embers, for example, are currently ranking in Romance but also in Literature & Fiction (Women’s Fiction > Contemporary Women) on Amazon.com. I don’t worry about categorisation when I write, and when I am asked ‘What kind of books do you write?’, I reply with what one newspaper reviewer said of my debut novel: ‘Romance like Hollywood used to make.’ That would make a wonderful category in itself, don’t you think?