10 facts you may not know about dictionaries

10 facts you may not know about dictionaries

10 facts you may not know about dictionaries

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

One of my hobbies is reading dictionaries; not cover to cover, because that would take an age, but dipping in and out. I love to learn about languages – both French and English, because I am bilingual. I especially love etymology, which is the study of the origin of words and the way in which their meanings have changed throughout history.

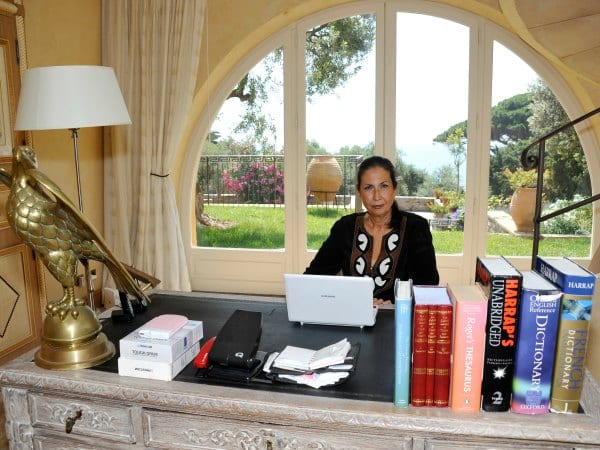

I have several dictionaries on my desk (pictured) which are well-thumbed. I never throw out a dictionary, even when it is old and fraying; they are the most soulful of books, I think, veritable treasure troves of learning. Along with general dictionaries, I have those for bilingual translation, synonyms (thesauri) and rhyming – not because I am a poet, but because I love the rhythm of rhyme.

Today, for fun, I am sharing ten things I have learned about dictionaries, some of which may just surprise you.

1. Dictionaries in various forms have existed right back to the earliest writings, but they were not so-called. Englishman John of Garland – graduate of the Universities of Oxford and Paris and master at the University of Toulouse – first coined the term ‘dictionary’ in 1220. He called the book he had written to help readers of Latin the Dictionarius.

2. The first single-language English dictionary was published in 1604 by a teacher named Robert Cawdrey and entitled Table Alphabeticall. At the time, advances in literature, science, medicine and the arts were creating all kinds of new words, and Cawdrey endeavoured to capture these and bring some order to the English language. The book had no words beginning with J, K, U, W, X or Y. A copy of this book is held to this day by the Bodleian Library, Oxford (a wonderful place to visit, I may add, if you ever have the chance).

3. Samuel Johnson laid the foundations for modern dictionaries. In 1755 he published the first really reliable modern (for its time) dictionary, A Dictionary of the English Language. It was so good that it was the standard dictionary for more than a century (until Oxford University began on their great work – see below). Samuel’s entries were sometimes colourful; ‘excise’, for example, was defined as ‘a hateful tax collected by wretches hired by those to whom excise is paid’, and ‘dull’ was defined as ‘not exhilarating, not delightful: as, “to make dictionaries is dull work”’.

4. The Oxford English Dictionary – in print to this day, and right here on my desk – was first published in 1928 in no less than 12 volumes, after 50 years’ work. Today, the dictionary is still widely regarded as the go-to source, with quarterly updates of new words (published at http://public.oed.com/whats-new/). Interestingly, though, back when it was first compiled, one of its main contributors was a man named William Chester Minor from his room in a mental asylum, in which he had been incarcerated for murder. To this day, people are invited to contribute to the dictionary: http://public.oed.com/the-oed-appeals/about-the-oed-appeals/.

5. Noah Webster spent 27 years researching and compiling his American Dictionary of the English Language, and to do so he learned some 26 languages. The final published work contained 12,000 words never before contained in a dictionary!

6. Dictionaries began as prescriptive: the compiler laid down hard-and-fast rules. For example, Noah Webster decided that color should be the American spelling for the British English colour, and center the spelling for centre. These days, dictionaries are more descriptive, exploring usage rather than decreeing it. Basically, those who compile dictionaries don’t necessarily approve of words, they simply report the words that people are using, and how.

7. Lexicography is the word used to describe the study of dictionaries. In fact, no one thought to study them until the 20th century. A man named Ladislav Zgusta, professor of linguistics and classics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, was the first to write a guide to lexicography in 1955, and he is seen as the godfather of the field.

8. All dictionaries are out of date. As Samuel Johnson put it, “Dictionaries are like watches, the worst is better than none, and the best cannot be expected to go quite true.” Because language is constantly evolving, no dictionary can keep perfect pace. Still, there is a lot that can be learned from any dictionary.

9. A dictionary is a wonderful tool for a writer, but it does not teach one to write. As Jorge Luis Borges wrote, “It is often forgotten that [dictionaries] are artificial repositories, put together well after the languages they define. The roots of language are irrational and of a magical nature.”

10. The longest word in an English dictionary is Pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis. It was conceived in 1935 by the then-president of the American National Puzzlers’ League, as a deliberate attempt to create the longest word in the English language. It worked: the synonym for silicosis, which refers to a lung disease, found its way into major dictionaries. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word thus: ‘an artificial long word said to mean a lung disease caused by inhaling very fine ash and sand dust’. A word well worth learning to impress, if not overly useful in conversation, correspondence and, in my case, romantic fiction…