Ancient Egyptian temple design

Ancient Egyptian temple design

Ancient Egyptian temple design

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The Temple of Philae

The landscape of Egypt was once dotted with temples, imposing structures that would draw the eye for miles around. There were two types of temple, each equally important. Cult temples were devoted to a particular god, such as the Temple of Isis on the island of Philae, while mortuary temples were for the worship of deceased pharaohs (who were incarnations of the god Horus in life and became the god Osiris upon death).

The vast majority of the temples that have survived to this day are from the New Kingdom period (c. 1570 BC) onwards. Comparing their designs shows that by this time, building on the legacy of the Middle Kingdom, a standard pattern had evolved. The Ancient Egyptians believed that many aspects of culture, from art to architecture, had been laid down by the gods and therefore should not be altered. Architects, then, followed common rules and incorporated certain features in their designs for more than a thousand years.

Position

Many of the New Kingdom temples are oriented so that the entrance faces the rising sun. They were commonly built on an east–west axis, perpendicular to the River Nile. A few were oriented with particular stars; one on Elephantine Island, for example, faces the rising star Sirius, which was associated with Osiris.

It was also popular to position a temple so that it would be inundated with water when, as happened every year, the Nile flooded. Then parts of the temple (never the sanctuary, which was built higher up) would appear to be rising from the primordial waters of Nun from which all creation sprang forth.

The grand approach

It was not only the design of the temple itself that could make it impressive; the approach – known as the processional avenue – really built the sense of wonder and magnificence. These avenues were usually lined with sphinx statues.

Avenue of sphinxes at the Temple of Karnak

The entrance

The temple would be enclosed by tall, thick mud-brick walls, to keep out uninvited visitors, and the entrance point was a pylon: a huge stone gateway. Some temples had a second pylon within, as at the Temple of Philae.

Second pylon of the Temple of Philae

There was often a back door as well, used by priests bringing the statue of a god on procession from the Nile.

The inner courtyard

This roofless area was surrounded by a colonnade of pillars, often intricately decorated. It also contained statues of pharaohs, nobles and priests (the Ancient Egyptians believed that a statue could be a vessel for a soul, and in this way they could be close to the god of the temple’s cult).

Courtyard of Ramses II, Temple of Luxor

The courtyard was the only part of the temple that everyday people were permitted to enter; the rest was off limits to all but the priests.

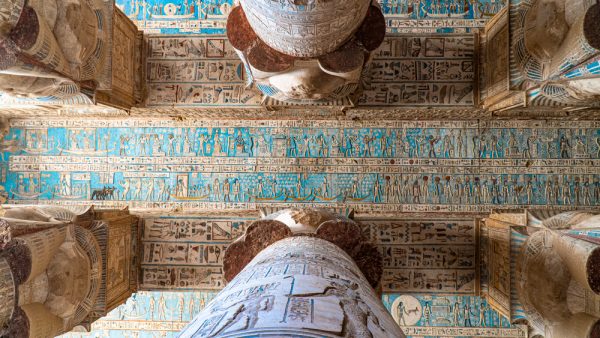

The hypostyle hall

From the pillared court you entered the hypostyle hall, an enclosed space with the ceiling resting on pillars. The ceiling was often painted blue, to represent the sky.

Ceiling of the hypostyle hall at the Temple of Hathor at Dendera

The sanctuary

The hypostyle hall led to the sanctuary, the very heart of the temple and its most holy place. Here was an altar, a small shrine and the cult statue which, it was believed, held the spirit of the god. There was also a shrine for the sacred temple bark (boat), which would be carried by priests on processions.

The sanctuary at the Temple of Edfu

Little natural light filtered into the inner sanctum; it was a dark and solemn place.

The sacred lake

This pool of water represented the primordial waters and was used for purifications and rituals.

Other buildings

The temple was a busy place, and within the walls you would also find outbuildings like stores, kitchens, stables and animal pens, and accommodation for the priests.

In the Ptolemaic period, it became popular to build a mammissi, which was a symbolic birth place for the pharaoh, representing their divine birth.

Obelisks

It was common for pharaohs to add to their predecessors’ temples with architectural flourishes. One such addition was the obelisk, a tall, pointed pillar that symbolised the sun. Eventually, most temples had at least two. They were carved from granite and their tips were often gilded.

Obelisks at the Temple of Karnak

Decoration

The architecture of the temple remained static for a long period of time, but that did not mean that each temple was identical – far from it. In the decoration of the temple there was great scope for a pharaoh to leave their mark (even if the temple was not theirs; they often redecorated a predecessor’s temple and claimed it all as their own work). Relief carvings and paintings depicted scenes in vivid detail, from offerings to the gods to the coronations of pharaohs. Some amazing examples have survived to this day, and from these we have learned so much about the history of this ancient civilisation.

An offering depicted at the Temple of Ramses II, Abydos

To think that temples like the one at Luxor have endured for more than 3,000 years! I hope you will have the opportunity to visit one someday and see for yourself how beautiful and impressive these temples were – and continue to be.

My ebook on the Temple of Philae, available to buy now

Picture credits: 1) Cyril Papot/Shutterstock; 2) Mountains Hunter/Shutterstock; 3) Alexandree/Shutterstock; 4) Paul Vinten/Shutterstock; 5) Merlin74/Shutterstock; 6) timsdad/Wikipedia; 7) Bist/Shutterstock; 8) inigolai-Photography/Shutterstock.