Book titles: What’s in a name?

Book titles: What’s in a name?

Book titles: What’s in a name?

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

For me, choosing the title of a book is one of the most fun parts of the writing process. But it is also one of the most important elements when it comes to book marketing.

Working with publishers for my fiction, I have come to understand that the title is not merely the linchpin of the work, embodying its sentiment and theme, and an expression of the author’s writing style. It is a tool for marketing.

Usually, I entitle a book long before I start writing it; in the dreaming and planning and research phase. That title sits with me for the long months that I write, and then is prominently displayed at the centre of page one when I send the manuscript to my publisher. The publisher’s marketing department then considers the title in terms of marketability:

Is it memorable?

Is it in keeping with the ‘Hannah Fielding’ brand?

Is it suitable for the genre?

How unique is it?

The last question is the most important. I have discovered that while ideally your book title is unique, it does not have to be. No copyright exists on titles, and although the English language is vast, many evocative phrases and words are favoured by writers (for an example, search for the title ‘Caught in the Middle’ in an online bookstore; so many results are returned!). Still, you don’t want to discover that your novel shares a title with another book published recently in the genre.

Or do you?

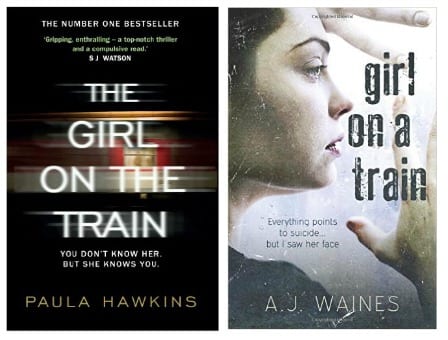

A recent news story in the Wall Street Journal that caught my eye concerned the novel The Girl on the Train. Paula Hawkin’s thriller was the breakthrough bestseller of 2015, selling more than 6.5 million copies worldwide. It has a record 37,000 reviews on Amazon, and is set to be made into a film Emily Blunt and Justin Theroux.

Such a high-profile book has garnered a lot of interest and publicity, so it is unsurprising that many readers have searched online for the book, and bought it to read. But have they in fact bought The Girl on the Train? It turns out that many have mistakenly bought Girl on a Train, a completely different thriller by author Alison Waines. The result? Girl on a Train has topped charts worldwide, sold tens of thousands of copies and received hundreds of reviews.

A similar phenomena occurred in 2013 when Stephen King published a book entitled Joyland. This title was not unique, and author Emily Schultz saw a surge of sales for her book by the same name. According to the Wall Street Journal:

[Ms Schultz] estimates she made about $3,200 on her accidental association with the prolific author. The blog went viral, and she says it boosted sales of her next book, “The Blondes.”

“It opened up a new audience for me,” she said.

Author Liam Callanan had the same experience when the novel Cloud Atlas hit the big screens in a film. He wrote that his novel, The Cloud Atlas, ‘zoomed to a triple-digit Amazon ranking’, but that he had to deal with emails from people writing ‘to ask why the book doesn’t match the movie’.

These stories are examples of serendipitous connections for less-well-known authors. But that doesn’t mean the authors in question always feel comfortable with the connection. Ms Waines, for example, reached out to a book club she heard was reading her book, assuming they’d ‘got the wrong one’. Happily for her, they hadn’t: and they gave her book a wonderful score.

It is notable in these stories that the relatively unknown books came first, before the famous novels were released with the same or very similar title. Attempts to ‘work the system’ and deliberately copycat titles are roundly condemned by readers, who feel deceived.

The moral of the story? Don’t worry about what anyone else is doing; just come up with your own title, the one that best suits the book. Then, having checked that you haven’t been pipped to the post, publish your book. If another work should appear someday and a connection form, so be it: but serendipity is always a gift from the universe, not something to be created and controlled.