Egyptology: an enduring fascination

Egyptology: an enduring fascination

Egyptology: an enduring fascination

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Egyptology is the study of Ancient Egypt, encompassing its culture, history, language, religion and architecture.

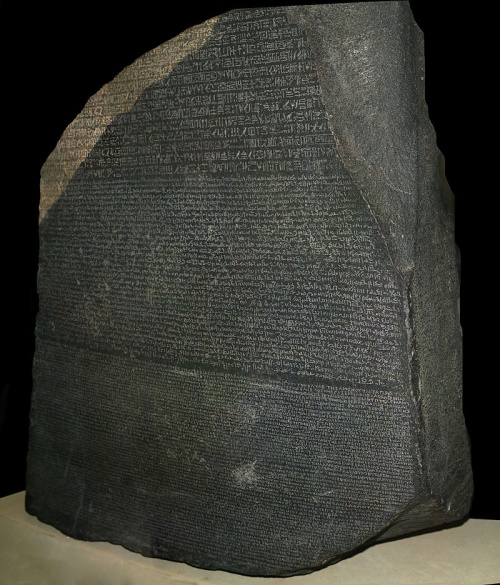

We can trace the origins of modern Egyptology back to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799. It dates back to the Hellenistic period and is inscribed with a decree in Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and demotic (a cursive form of hieroglyphics), and in Ancient Greek. The stone was brought to London and displayed in the British Museum (where it has remained since), and it stirred great excitement amongst scholars for it offered a key for translating the Ancient Egyptian scripts.

During the late 1700s, Napoleon Bonaparte had taken control of Egypt, and his savants, a group of some 160 scholars and scientists, made it their mission to study and catalogue what they could learn about Egypt. The result was Mémoires sur l’Égypte, a four-volume work published by the Egyptian Scientific Institute between 1799 and 1803, and the Description de l’Égypte, a series of volumes published between 1809 and 1829.

For the first time, people outside of Egypt had access to information on the country’s history, and the fascination for this ancient civilisation, with its temples and tombs and deities and kings, was sparked. Even better, in 1826 Jean-Francois Champollion published the first dictionary of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, and at last the mysteries of inscriptions on walls in temples and tombs could be unlocked.

Egyptologists flocked to Egypt in the 1800s and early 1900s, galvanised by the thought of solving mysteries and uncovering ancient treasures. Early Egyptologists included Champollion, Thomas Young, Ippolito Rosellini, Karl Richard Lepsius and Flinders Petrie; the latter established several important archaeological techniques and a dating system that is still in use today. Egyptology became all the rage for intellectuals. Even Florence Nightingale travelled to Egypt and was inspired spiritually by her experiences touring ancient sites. She wrote of the Abu Simbel temples, built by Ramses II:

‘Sublime in the highest style of intellectual beauty, intellect without effort, without suffering… not a feature is correct – but the whole effect is more expressive of spiritual grandeur than anything I could have imagined.’

The Abu Simbel discovery was made by a traveller, Jean-Louis Burckhardt, in 1813. All he saw then was the head of a statue; the rest was buried in sand. In 1817 Egyptologist Giovanni Belzoni began clearing the sand; he had once been a circus strongman and did much of the work himself. But whenever he cleared sand from the façade of the temple, the wind blew it back. It wasn’t until 1871, financed by a benefactor, that he managed to find the entrance. How he must have felt, the first man in so many years to enter that sacred place.

The story of the Abu Simbel temples discovery is typical of so many discoveries. In the 1800s and 1900s, many, many sites were excavated in Egypt and many tombs, temples and relics unearthed. Mummies too, of course: the discovery of the Royal Mummy Cache of 1881 was especially significant, as inside the tomb were many New Kingdom mummies, including Ramses I and Ramses II. This tomb was actually discovered by a family of tomb-robbers and one of them gave up its location (eventually, after a good deal of wrangling with the authorities). Sadly, grave-robbing and the illegal trafficking of antiquities goes hand in hand with Egyptology – and this is a dark world I explore in Song of the Nile.

Probably the most famous breakthrough in Egyptology was the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Howard Carter, along with his benefactor Lord Carnarvon, had been searching for this missing tomb in the Valley of the Kings for years, and in 1922 they found it. What they saw when they entered the tomb was awe-inspiring – gold everywhere, in shrines, in jewellery, in the sarcophagus and in the death mask of this ancient king.

Carnarvon died a few months later, having developed blood poisoning from a mosquito bite, and the British media reported on the ‘Curse of Tutankhamun’, whipping up the dramatic notion that to disturb a king’s tomb is to risk dire punishment. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame contributed to this by suggesting that Carnarvon had died because he disturbed ‘elementals’ created by priests to guard the tomb. Several other people connected to the Tutankhamun discovery died, but Howard Carter lived until the late 1930s. Still, the ‘curse’ made for a great story and boosted interest in Egyptology.

To this day, explorations continue in Egypt, and while they may not all be as thrilling as the Tutankhamun find, they have so much to teach us. In 1997, for example, underwater excavations revealed the city, flooded 1,200 years ago by a devastating tidal wave, which was the home of Anthony and Cleopatra.

Each year more and more is discovered, jigsaw pieces to help us piece together an ancient world. So long as there is more to unearth – and it is hard to imagine an end to the discoveries buried by sand and sea – then Egyptology will continue to be a source of great passion, pleasure and interest for many.