Maktoub: That which is already written

Maktoub: That which is already written

Maktoub: That which is already written

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

If you have read my novels, you’ll know I have a keen interest in philosophy, especially how it relates to destiny versus self-autonomy.

The Moors believed in maktoub, which means ‘already written’; these days in the West we often express the concept as ‘written in the stars’.

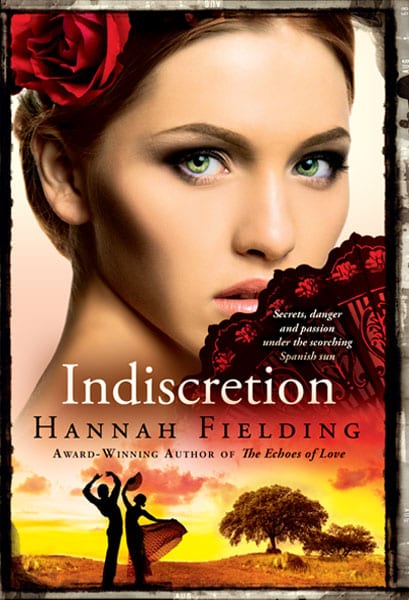

In my novel Indiscretion, maktoub is a powerful force that is hard to escape, much less dismiss as incredible. Here’s a friend of the heroine, Alexandra, reassuring her that she can trust to destiny:

Fate will give you both a second chance. The world is full of the unexpected! There is some truth in the old Moorish saying: if it’s maktoub, written in the unknown, that you are meant for each other, then neither the oceans, nor the deserts, nor the whole universe will be able to keep you from one another. And you will meet again.

Alexandra tries to take comfort from this idea that all will come right, and she can relax and put her faith in maktoub. But events conspire to thwart her will, and before long she is uneasy:

It was as though invisible influences were at work, inexorably playing havoc with her life, preventing her from leaving Spain. This was the second time fate had interfered with her plans. She thought of the Moor’s maktoub, and of the gypsies. Was all of this ‘written’?

Indiscretion: available to buy now

In Song of the Nile, those around Aida seem convinced that she is destined to marry Phares. But is she, or does she make her own choices? Al maktoub alal guibeen la bodda an tarah el ein, her friend tells her: What is written will be fulfilled. Aida doesn’t know whether she wishes this, or fears it.

In The Echoes of Love, fate is central to the developing relationship between Paolo and Venetia. Paolo tells Venetia that in accordance with the idea of maktoub, ‘Arabs say that from the day you are born, the name of your sweetheart is invisibly engraved on your forehead.’ He recites for her a verse from Omar Khayyam:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: not all the Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

Venetia is unconvinced: ‘Fate is the superstitious mind’s way of misinterpreting coincidence,’ she tells Paolo. ‘We forge our own destiny.’ Then she meets a wise man, Ping Lü, a fortune teller. He tells her:

‘Believe in Fate. We say in China that what is destined to be yours will always return to you, and that when Fate throws a dagger at you, there are only two ways to catch it: by the blade or by the handle.’

Eventually, Venetia lets go and accepts her fate:

Fate would arrange everything at the end; her heart told her so. She had converted to its power; the only thing she needed to do now was to believe in her lucky star.

What do you think: is there truth in fate, maktoub, destiny? Are we always exactly where we are meant to be, and so we can relax, knowing we need not struggle but can accept? Or is it our right to forge our own path; to be, as William Ernest Henley wrote in ‘Invictus’, ‘the master of [our] fate… the captain of [our] soul’?

Photo credit: TypoArt BS/Shutterstock.com.