Neuschwanstein: The fairy-tale castle

Neuschwanstein: The fairy-tale castle

Neuschwanstein: The fairy-tale castle

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Neuschwanstein Castle, Bavaria, Germany. Quite simply one of the most beautiful castles in the world. Not only is the setting spectacular, affording panoramic views over forest and plain, mountain and lake, but the castle itself… it is like something out of a storybook.

Indeed, sometimes the castle is straight out of a story. If you are thinking Neuschwanstein looks familiar, you may well have seen it in films like The Great Escape (1963) and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), and as an inspiration for the castle in Sleeping Beauty (1959), which has since been used as the logo for Disney.

Of all the castles I have visited in the world, Neuschwanstein has to be the most romantic and most certainly the most dramatic. When I walked around the rooms of the castle, I felt great respect for the vision upon which this place was built – the vision of King Ludwig II.

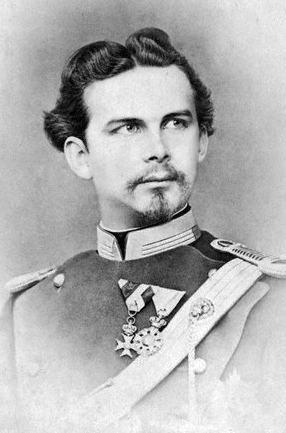

Ludwig was a king with soul – a dreamer, a romantic. He loved poetry and art and the theatre and music, especially the operas of Richard Wagner; indeed, Wagner was his hero. When Ludwig ascended to the throne of Bavaria in 1864, aged 18, he was not very interested in being a mighty ruler; his passion was creative projects, including the construction of several impressive palaces, of which Neuschwanstein is the most iconic.

Ludwig II, c. 1874

Through his 22-year reign, Ludwig became increasingly reclusive, seeking ‘ideal monarchical poetic solitude’ in which he could lose himself in his fantasies. Neuschwanstein Castle was to be a sanctuary for him.

Ludwig’s father, Maximilian II, had built a castle in the village of Hohenschwangau, and this was where Ludwig had grown up. He loved the location – the views, the remoteness – and decided he would build a better castle. In a letter to Wagner he wrote:

It is my intention to rebuild the old castle ruin of Hohenschwangau near the Pöllat Gorge in the authentic style of the old German knights’ castles… the location is one of the most beautiful to be found, holy and unapproachable… this castle will be in every way more beautiful and habitable than Hohenschwangau further down; [the gods will] come to live with Us on the lofty heights, breathing the air of heaven.

Ludwig, a big fan of medieval legends, designed the new castle to be like one from the Middle Ages, in the Romanesque style. The cornerstone was laid in September 1869, and by the time Ludwig died, in 1886, it was still not complete. Sadly, Ludwig did not get to live in his fantasy castle for long before his death, which came soon after he was deposed. (That is a story in itself: in short, poor Ludwig was declared insane, removed from power and died the next day of, apparently, suicide. Historians have since questioned whether ‘Mad King Ludwig’ was in fact simply shy and eccentric, not mentally ill, and whether he was actually murdered.)

Ludwig had never intended Neuschwanstein to be opened to visitors, but just weeks after his death the new ruler of Bavaria, Luitpold, Prince Regent, ordered that the castle be opened up in order to bring in revenue. Since then, the castle has remained a popular attraction for visitors to Bavaria; some 6,000 people visit each day in the summer.

Today, a programme of works is underway to restore the interior of the castle to its 19th-century splendour. The decoration in the rooms really is breathtaking. Ludwig had dedicated the castle to Wagner, and the interior artworks depict scenes from his operas – which in turn are from medieval legends. The Throne Room is particularly beautiful; the castle website describes it as ‘built as a monument to kingship and a copy of the legendary Grail hall’.

Views of the Throne Room

‘Neuschwanstein’ translates to ‘New Swan Stone’, and the swan is a recurring theme in the castle. The swan featured in the heraldry of the knights of Schwangau (who had owned the original Hohenschwangau Castle), and Ludwig identified strongly with Lohengrin, from the German Arthurian Holy Grail story, which inspired Wagner’s opera.

In the legend of Lohengrin, the knight is sent to defend a beautiful maiden, Elsa, but there is a condition to his help: she is forbidden to ask his name. The two marry (from this part of Wagner’s opera we have the famous ‘Bridal Chorus’), but of course the inevitable happens. The love story ends with Lohengrin leaving the inquisitive Elsa, sailing away on a boat pulled by swans.

I thought of this sad ending when I visited Neuschwanstein; I felt a sort of melancholy to consider Ludwig’s own ending. After their first meeting, Wagner had written of Ludwig:

He is unfortunately so beautiful and wise, soulful and lordly, that I fear his life must fade away like a divine dream in this base world … You cannot imagine the magic of his regard: if he remains alive it will be a great miracle!

One could say that Ludwig’s character was his own downfall: his sensitivity, his introversion, his poetic soul, his preference for fantasy over reality. But through all of these qualities, he left behind a truly remarkable legacy: a dream made real.

Picture credits: 1) DaLiu/Shutterstock; 2) public domain/Wikipedia; 3) Nico Benedickt/Unsplash; 4) Patryk Kosmider/Shutterstock; 5) Lokilech/Wikipedia; 6) Alessandro Colle/Shutterstock.