The origins of English words

The origins of English words

The origins of English words

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

I am a writer and I speak three languages fluently, so I have a natural interest in linguistics (the study of languages). But since I learned English, I have become fascinated with etymology: the study of the origin of words and the way in which their meanings have altered over time.

English is a very interesting language to explore. It has far more words than any other language: according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the English language currently includes around 171,000 words. (A further 47,000 exist but have fallen out of use.) Clearly, that is a vast collection of words, so where have they all come from?

The answer is, the English have had a long tradition of borrowing words from other languages. Some words originate from Old English (dating back to before the Anglo-Saxons settled in Britain), but then there are also influences from Old Norse, Old French, Latin and Greek, other Romance languages and, eventually, languages from territories conquered for the Empire. (Strangely, very little was taken, though, from the long-spoken languages native to Britain of Welsh, Irish and Scottish Gaelic.)

Did you know that pharaoh, a word I use commonly in my novel Song of the Nile, is taken from the Egyptian pr-‘o, meaning ‘great house’? That grin is an 11th-century word that meant ‘to bare the teeth in pain or anger’ (which is how we got the expression ‘grin and bear it’)? That happy is derived from ‘hap’, introduced in the 13th century and meaning fortune or chance (hence we have hapless, happen and perhaps)? That garden is from the Old French jardin and is itself the origin of the word yard? That enthusiasm comes from the Greek enthous, meaning ‘possessed by a god, inspired’ (from theos for god)?

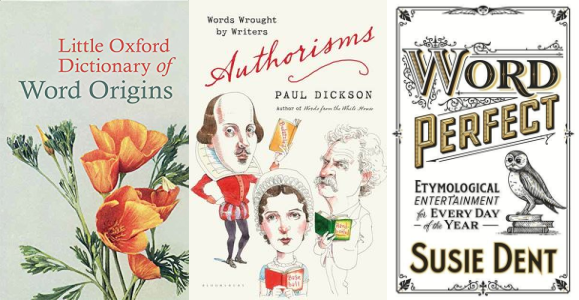

These and many other words feature in the Little Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins, which is just wonderful – a dictionary you really can read from cover to cover.

But I have not yet accounted for a great number of the many words of the English language. British people did not only borrow from other languages, but invented their own words, of course – and no one enjoys doing so more than writers.

Shakespeare, for example, coined more than a thousand words, like bedazzled, lacklustre, critical, dewdrop and fairyland. John Milton gave us awestruck and pandemonium. Samuel Taylor Coleridge gave us soulmate. William Wordsworth gave us pedestrian (though would no doubt wish to be remembered for coining a more poetic term). For more ‘authorisms’, do take a look at the book by that title written by Paul Dickson.

If this article has piqued your interest (incidentally, from the Middle French verb piquer, meaning ‘to prick’), you’ll find that there are many books you can explore on etymology. I found Word Perfect: Etymological Entertainment Every Day, by lexicographer Susie Dent, to be a fun and enlightening read. Who knew that the meaning of grammar once encompassed occult magic?!

Photo credit: aga7ta/Shutterstock.