Don’t look back! A lesson from Orpheus and Eurydice of Greek mythology

Don’t look back! A lesson from Orpheus and Eurydice of Greek mythology

Don’t look back! A lesson from Orpheus and Eurydice of Greek mythology

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

I find inspiration for my writing from all kinds of sources. For Burning Embers, I was inspired by the poetry of French poet Leconte de Lisle; for The Echoes of Love, an experience in the Piazza San Marco, Venice, sparked the idea of a city with two faces; for my Andalucían Nights trilogy, the passion and pride inherent in the flamenco fired me up to write a tempestuous love story.

My new novel, Aphrodite’s Tears, was born of a lifelong fascination with Greek mythology and a love of the Greek islands, and all kinds of things gave me ideas for the story, from olive-growing (see https://hannahfielding.net/staging/1129/creating-my-own-olive-oil/) to jewellery-making (see https://hannahfielding.net/staging/1129/ilias-lalaounis/). But one inspiration goes way back; in fact, it’s been haunting me for decades.

Here is the song, from the Swinging Sixties, by a French singer called Erik Montry. It’s called ‘Eurydice et Orphee’:

The singer is singing of falling in love at first sight with a girl in a crowd, in Piraeus, Greece. But no sooner have the two come together than he loses her again, and he is left with only the hope that he will see her again someday.

They are Eurydice and Orpheus, Erik Montry sings, and this conveys two meanings: 1) that the couple had fallen in love; and 2) that they were brought together only to be separated. For the Ancient Greek story of Eurydice and Orpheus is not one with a happy ending.

According to legend, Orpheus (son of Apollo) and Eurydice (a nymph) were madly in love, and theirs was a happy marriage. Until, one day, Eurydice was killed by a viper. Orpheus was beside himself. He took up his lyre and played and sang with such intense grief that the gods were moved, and they urged him to undo what was done: to rescue his lost love.

Orpheus made the journey to the Underworld, where he played and sang for Hades and Persephone. They, too, were moved – and swayed by Orpheus’s clear devotion to his wife. Hades told Orpheus that he could take Eurydice back, but with one condition: he must walk in front of her on his way out of the Underworld, and he must not look back until he reached the mortal realm.

Orpheus did as he was told. Until, just as daylight came into view, his doubts overwhelmed him. He could not hear or feel the spectral woman behind him. Had Hades tricked him? Was his wife there at all?

He risked a quick glance behind, and he saw…

… his beloved there after all, but quickly fading from sight, claimed for all eternity by Hades.

Poor Orpheus – can you imagine how he felt? He had destroyed his one chance of happiness; he had lost Eurydice. Ultimately, the only way he could be with her now was through his own death – and this is how most ancient writers ended the story, with Orpheus killed by wild beasts, by the maenads (mad women) or by a lightning-bolt courtesy of Zeus.

A sobering lesson indeed on perseverance, faith and not disobeying the god of the Underworld!

The story of Eurydice and Orpheus has been inspiring thinkers and dreamers for many centuries. Here, for example, is Auguste Rodin’s 1893 sculpture of Orpheus trying so hard to resist the urge to look back.

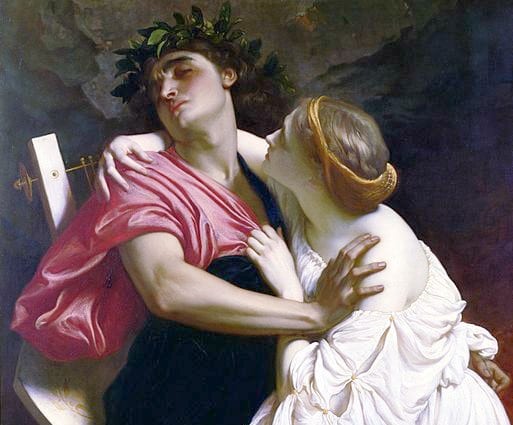

My favourite interpretation of the story is the 18th-century opera Orfeo ed Euridice by Willibald Gluck. In this version, Eurydice, following her husband out of the Underworld, is hurt that he won’t look at her, and she takes it to mean he does not love her. The emotion is captured so well in Frederic Leighton’s 1864 painting of the lovers:

Eurydice sings of her sorrow, and it breaks Orpheus’s heart: he just has to set her straight – of course he loves her! He turns… she is gone. At this point, the distraught Orpheus decides to take his own life, but Cupid (who made the ‘don’t look back’ rule) intervenes. As a reward for Orpheus’s enduring love, Cupid resurrects Eurydice, and all is well.

Of course, as a romantic, I far prefer this ending, but I wonder: what happened next? How did Eurydice and Orpheus get on once they were reunited? How, indeed, would the girl and the guy of Erik Montry’s song have fared had they found each other again in the crowd?

This wondering is what sparked the idea for my novel Aphrodite’s Tears. Oriel and Damian meet by chance one evening on a beach. Both have plenty they wish to escape. Both are wrestling with difficult emotions. Both feel an instant and powerful attraction to the other. They connect; they spend a night together – and then, come the next morning, they separate.

Six years later, I bring Oriel and Damian together again. How will the separation have affected them? How will the reunion work out? Will they keep looking back, or will they face the future – together?

Ultimately, are this Eurydice and Orpheus doomed to be torn apart, or will Cupid intervene and grant them their own happy ending?

The movement in the video brings back memories. I too like the last version of the story of Orpheus Eurydice. The story could have been written as one of Aesop’s Fables. It made me think of the Biblical story of Lot’s wife being turned to stone for looking back at Gommorah.