To sleep, perchance to dream

To sleep, perchance to dream

To sleep, perchance to dream

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Dreams are necessary to life. – Anais Nin (source)

Since ancient times, dreams have been held to have importance. The Mesopotamians thought that while sleeping a person’s soul left the body and travelled to a dream realm, and the Chinese thought a part of the soul did this. The Romans believed dreams were messages from deities, and that they told of the future. They so wanted these messages that they created sleep sanctuaries where people would repose on special beds designed to induce dreams. The Greeks took the same path, and worshipped a god of dreams named Morpheus, a winged daemon who supposedly gave prophecies to people slumbering in his temples. The Bible, of course, is full of dreams in which God speaks, and Native American cultures often saw dreams as messages from those who had passed on.

A discussion through history on the meaning of dreams that has always fascinated me is known as the dream argument. The fourth-century philosopher Zhuang Zhou told of a dream in which he was a butterfly. When he woke up, he could not decide: had he just come out of dreaming he was a butterfly, or was he a butterfly who’d just begun to dream he was a man? This has become a great philosophical question, explored by great minds like Plato and Aristotle, and most notably by René Descartes in his Meditations on First Philosophy.

Are you the butterfly or the person? (source)

Dreams feature in all of my novels, for I see them as an important way to explore a character’s thoughts and emotions, particularly on the subconscious level. In The Echoes of Love, for example, both Venetia and Paolo are haunted by dreams that are difficult to interpret but seem to be imparting important information. In Song of the Nile, Aida’s attraction to Phares, which she tries to stifle in herself, comes to the fore in her dreams.

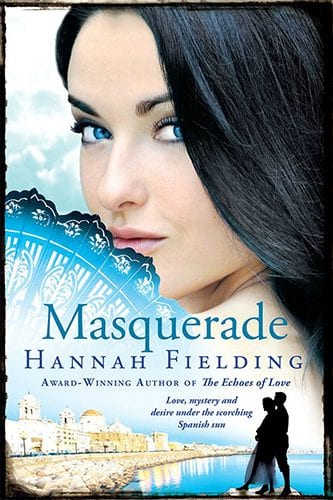

For these characters, it is apparent that their dreams are just that. But in my novel Masquerade, I take a step further in exploring the significance of dreams.

Where does the dream end and reality begin?

Can the dream not only come true, but be true?

These are questions I had in mind as I wrote Masquerade. What truths lie in the dream is a question that plagues the heroine Luz, who is attracted to two men – the wild gypsy Leandro and the sophisticated gentleman Andrés – but has a sense that neither is quite what he appears to be.

Masquerade: available to buy now

It is after meeting Leandro that Luz first awakens from an unsettling dream. That she has dreamed at all is unsettling; she does not usually, and when she does, she remembers nothing come the day. But when she awakes this morning the details of her strange dream are disturbingly vivid. Until that point, she has always regarded dreams as meaningless nonsense, even though in Andalusian culture, where superstitions abound, they are regarded as many as omens. Now, intrigued and ill at ease, she decides to ask her housekeeper Carmela for her interpretation. She explains:

‘I dreamt I was on a vast dark plain, in the middle of which a bright fire was burning. I went up to it with a mixture of fear and awe. It became brighter and brighter as I approached and then, even though I was scared, without the least hesitation I walked right into it. The flames were all around me. They licked me but didn’t burn, and I wasn’t afraid anymore. I walked through the fire and as I emerged from it I saw a shadow, the silhouette of a person. I couldn’t distinguish whether it was a man or a woman. The figure was a shape without features. It took my two hands and together we rose into the sky towards another fire which, when we reached it, suddenly turned into a sun.’

Carmela is certain that this is un sueño maravilloso, a wonderful dream, which means that soon Luz’s heart will be burning with a very powerful fire, un gran amor y pasión. Luz is sceptical, and yet the dream comes again and again, and soon the fire is all-consuming and she cannot walk out of the flames.

Later in the book, after she has met Andrés, the dream that haunts Luz’s nights changes. She is in the Garden of Eden, and Leandro is there – or is it Andrés? She is not certain – and he eludes her, moving swiftly through the magical paradise.

All through her dream she could glimpse his glistening bronzed figure appearing then disappearing behind trees and shrubberies, only to resurface next to a marble colonnade and vanish again suddenly without warning, always inaccessible.

I recall, as I wrote, being inspired by the vivid colours of Henri Rousseau’s final painting, Le Rêve (The Dream).

Le Rêve (source)

But the calm and benign beauty in that first dream is shattered. Later, the dream transforms and in the Garden are both Leandro and Andrés, joined at the shoulder, playing hide and seek with Luz through the trees.

They were the twins, and each wore the Gemini half-mask. Suddenly they seemed to be moving towards her. As they neared, their image gradually merged into one, with the mask covering the whole face until the irises behind it were so close to her, glancing through the leaves, that a green eye and a black one stared with saturnine mockery into the horror of her own.

How much of Luz’s increasingly intense and troubling dreams is meaningful? And what meaning should be ascribed? Are the dreams omens, as Carmela would have her believe? Has the modern-day Morpheus bestowed on Luz guidance for her future?

Or are the dreams, in fact, the whisperings of Luz’s subconscious, as Sigmund Freud would have interpreted? Does Luz already know the truth, deep down? If so: will she have the courage to face what is real, to remove the mask of the masquerade?