The Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The tomb of a pharaoh in Ancient Egypt was incredibly important, so important it was built over many years during their lifetime in preparation. The tomb was a House of Eternity, a sacred resting place where the deceased king would dwell in the afterlife. It would be intricately decorated with wall and ceiling paintings and filled with all manner of items for the king’s use in the afterlife – items that were great treasures indeed.

Tomb robbing became a real problem. When it was obvious where the tomb was, because it was marked by a grand monument, the temptation was great for treasure-seeking thieves. No king wanted his resting place to be violated, and so during the time of the New Kingdom (c. 1570–1070 BC) a new tradition developed: build a grand mortuary temple as a memorial to the king and a place for people to leave offerings and make prayers, and entomb the king elsewhere, someplace secure, someplace secret.

The chosen location was a valley on the west bank of the Nile across from Thebes (modern-day Luxor) in the Theban Hills.

An aerial view of the Theban Hills

Not only was this an isolated spot that was difficult to access, but it was watched over by a pyramid: the peak al-Qurn.

The ‘pyramid’ of al-Qurn

This valley became the Place of Truth, or, according to hieroglyphics, the ‘Majestic Necropolis of the Millions of Years of the Pharaoh, Life, Strength, Health in the West of Thebes’.

The tombs here were cut into the rock and there are no fancy facades, no elaborations to suggest ‘Here Lies a Great Pharaoh’. Most of the entrances were cut into the valley floor, where the sand would cover them; those that were cut into the cliffs were hard to access and hidden well. The tombs were made by workers who lived in the nearby workers’ village of Deir el-Medina, and all work was conducted on the quiet. The adviser of Thutmose I noted that: ‘I saw to the excavation of the rock-tomb of his majesty, alone, no one seeing, no one hearing.’

Still, despite all the secrecy, all the tombs were robbed in antiquity. One tomb, KV9, even features graffiti dating from 278 BC; apparently, the valley was a popular spot for Roman tourists. During the 21st Dynasty priests moved some bodies to a store in order to protect them, leaving some tombs empty. Eventually, flooding caused many tombs to be buried under debris.

Tomb entrances unearthed in the valley

With the dawn of modern Egyptology following the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, the Valley of the Kings naturally became a source of great interest. Many people travelled here to explore the valley, to learn more from the known tombs, and of course to search for as yet undiscovered tombs. Of all the discoveries in the Valley of the Kings, the most famous is that of Howard Carter. Though he had been told that ‘The Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted’, he kept searching, and in November 1922 he opened the tomb of Tutankhamun. It was by far the best preserved tomb of the valley and contained many, many treasures, along with the mummy of Tutankhamun himself.

Tomb of Tutankhamun

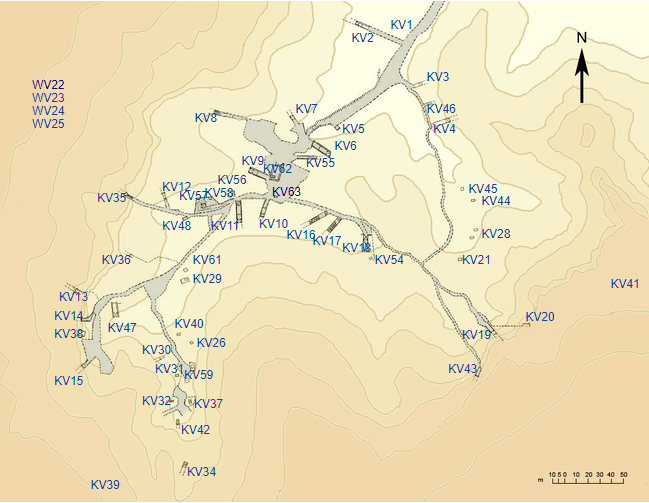

From all of the explorations in the valley over the past 200 years, we have built a good understanding of the necropolis. In fact, there are two valleys: the Eastern Valley has 63 tombs, and the Western Valley contains five tombs. The tombs are numbered according to the order in which they were discovered; WV signifies West Valley and KV stands for Kings’ Valley.

Map showing the locations of the tombs found in the valley

Only 23 of the 63 KV tombs are actually those of pharaohs; the rest were for officials and favourite children and wives (the latter were usually buried in the nearby Valley of the Queens, which contains more than 100 tombs). The owners of 20 of the Eastern Valley tombs and one of the Western tombs are unknown.

The Valley of the Kings was in use from the 18th Dynasty, and was especially popular in the 19th and 20th Dynasties. Kings from Thutmose I to Ramesses X had tombs in the valley, though some tombs are missing (or perhaps as yet unfound?); there is no tomb for Ramesses VIII, for example. Among the most famous pharaohs entombed here were Seti I and Ramesses II, known as Ramesses the Great.

Visitors to the valley never cease to be awestruck by the decorations inside the tombs. They are beyond compare.

Tomb of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI

Tomb of Ramesses III

These days great care is taken to preserve the tombs in this World Heritage site. Only 18 of the tombs are opened to the public, and these are opened on rotation. Carbon dioxide and humidity caused by visitors damages the paintings, and so in some places glass screens have been introduced, as well as dehumidifiers. Work is always ongoing to preserve these precious tombs – and, of course, to search for others. KV63 was only found in 2005, and KV64 as recently as 2011, so it is hopeful that there is much more to find besides. Imagine, another tomb as intact as Tutankhamun’s! How amazing that would be.

If you are interested in the Valley of the Kings, it is well worth exploring the website of the Theban Mapping Project. It provides so much detailed information on each tomb, including plans of the layout, and so many wonderful photos. I think you will enjoy looking through it. Beware, though: you may become completely engrossed and lose track of time, as I did!

Picture credits: 1) Jeremy Bezanger/Unsplash; 2) Marie Thérèse Hébert & Jean Robert Thibault/Wikipedia; 3) Anton Belo/Shutterstock; 4) Nick Brundle Photography/Shutterstock; 5) Wikipedia; 6) Whatafoto/Shutterstock; 7) agsaz/Shutterstock.

Awesome 👑