Victoria, Albert and their passion for Christmas

Victoria, Albert and their passion for Christmas

Victoria, Albert and their passion for Christmas

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

I have written before on the influence the author Charles Dickens had on Christmas traditions in Britain (and, indeed, beyond), thanks to the publication of his novella A Christmas Carol. This work was published in 1843, in the Victorian era, so-named for the queen on the throne at the time – and she and her husband also popularised Christmas and traditions of the festive season.

Christmas for Queen Victoria and Albert, Prince Consort, was a time of great happiness. The couple, if you remember, were very much in love; their marriage was no mere alliance between royal families but a love match. Christmas was a time to be together with their children, to celebrate, to feast and to give each other gifts, as they were so fond of doing.

Victoria and Albert on their wedding day, 1840

Albert did not, as is often believed, introduce the Christmas tree to Britain. The custom of decorating a tree originated in Germany and Albert was a German prince, but in fact Victoria herself had a German mother and the custom had been upheld in the court for some time. Even if Albert did not begin the tradition, however, he certainly embraced it with hitherto unknown gusto. He took on the task of decorating the trees at Windsor Castle himself, with candles and sweets and gingerbread.

The decorations created a wonderfully festive atmosphere, to the pleasure of the queen and her husband. On Christmas Eve 1841, Victoria wrote in her diary:

Christmas, I always look upon as a most dear happy time, also for Albert, who enjoyed it naturally still more in his happy home, which mine, certainly, as a child, was not. It is a pleasure to have this blessed festival associated with one’s happiest days. The very smell of the Christmas Trees of pleasant memories. To think, we have already 2 Children now, & one who already enjoys the sight, — it seems like a dream.

In 1847, Albert wrote:

I must now seek in the children an echo of what Ernest [his brother] and I were in the old time, of what we felt and thought; and their delight in the Christmas trees is not less than ours used to be.

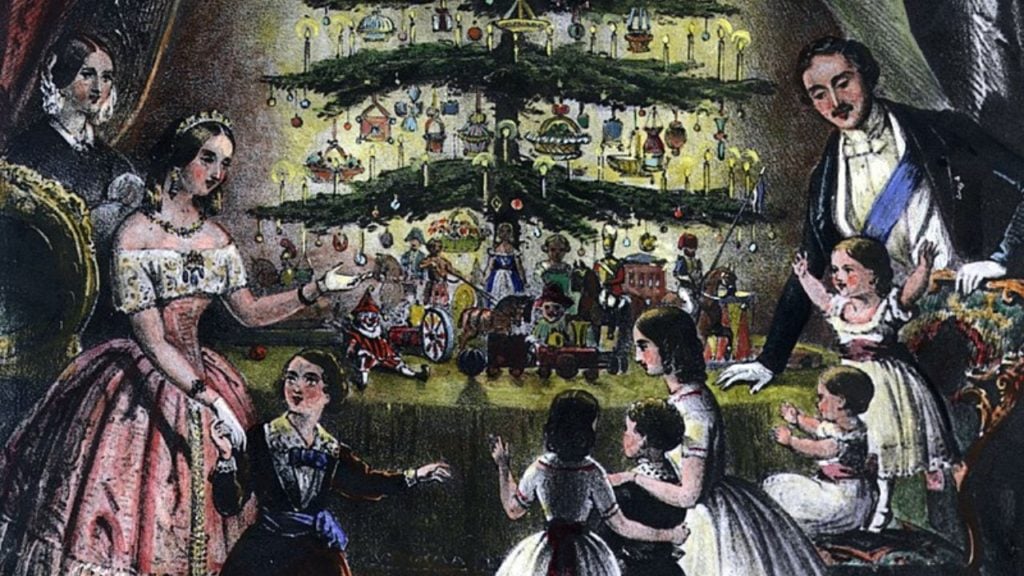

In 1848 the Illustrated London News published an engraving of the royal family around a decorated tree. This quickly popularised the idea of decorating Christmas trees in the home, though at first, as the Times reported in 1858, this custom was upheld by the wealthy or ‘romantic’. It also reinforced the idea that Christmas was a time for family and for festivity.

‘Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle’, Illustrated London News, December 1848

© British Library Board

According to Queen Victoria’s diary entry of Christmas Day 1852, on the menu were ‘turkeys, Baron of Beef, Plum Pudding & Mince Pies’. A festive bird was the centrepiece of the table at the time, though most people couldn’t afford turkey, and until the late nineteenth century goose was more common (hence Ebenezer Scrooge giving a goose to the Cratchits).

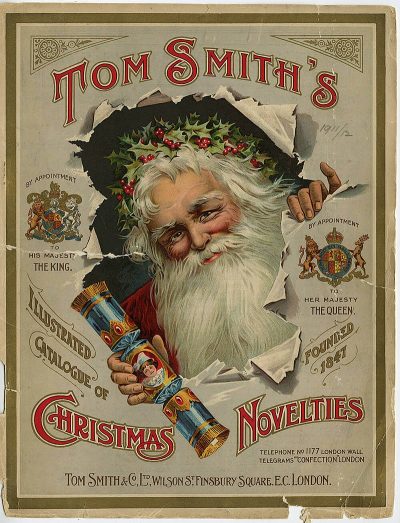

Christmas crackers may well have been on Victoria and Albert’s table as well. Reportedly, Queen Elizabeth II enjoyed pulling a cracker over the Christmas meal, and this is a tradition inherited from the time of her great-great-grandparents. The cracker was invented in 1847 by Tom Smith, who was inspired by the bonbons (wrapped sweets) he saw on a trip to Paris, and by the crackling of logs on the fire for the ‘crack’ sound. According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, ‘Along with a joke, gifts inside could range from small trinkets such as whistles and miniature dolls to more substantial items like jewellery.’ Come the twentieth century the Tom Smith Crackers company was still supplying crackers to the royal family via a Royal Warrant.

1911 catalogue for Tom Smith’s Crackers

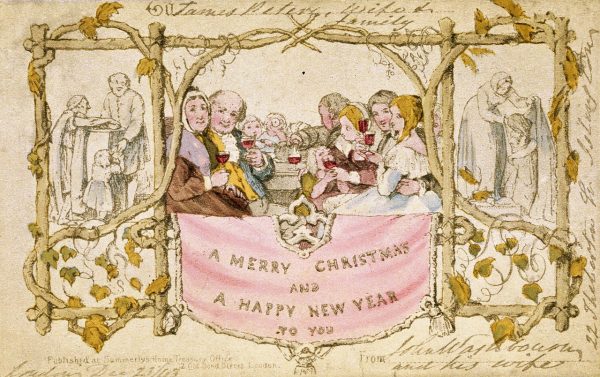

Apart from enjoying Christmas at home, Victoria was keen to spread the festive cheer, sending best wishes for the season via the newly introduced Christmas card. Henry Cole, future director of the V&A Museum, had made the first commercial Christmas card in 1843, printing a thousand cards designed by an artist to send instead of a letter and selling those he didn’t use.

The first commercial Christmas card, commissioned by Henry Cole, 1843

According to the Postal Museum of London, it was Queen Victoria who sent the first ever official Christmas card. The introduction of the Penny Post in 1840 paved the way for people to send cards far and wide, and by the end of the century advancements in printing made printed cards affordable for many. Queen Victoria would send cards to friends and family, members of her staff and her tenants. The British Museum has in its collection several cards sent by the queen and preserved by Queen Mary, wife of George V, who was the grandson of Victoria.

Sadly, Victoria’s beloved husband died in December 1861. Their last Christmas together at least was happy. On Christmas Eve 1860 she wrote:

Already this dear Festival returned again, & this year with true Xmas weather, snow on the ground & sharp frost. Albert & the Princes out shooting, but Louis preferred remaining with Alice. Walked down with them to the skating pond, where we found the other girls …

We came home after 4, then began the arranging of the present tables, which was most bewildering, but however at last with dear Albert’s great indefatigability, we succeeded …

Everyone seemed delighted with their present. I got charming & beautiful things. …

Al the dear Children worked me something, also Mama. As usual, such a merry happy night with all the Children.

After losing Albert, Victoria lost the joy of Christmas. She wrote in December the following year, ‘Christmas, formerly such a dear happy time, came so sadly before me.’ The anniversary of Albert’s death in December became what she called ‘the terrible 14th’, casting a shadow over Christmas. According to English Heritage, however, ‘her grandchildren would eventually restore her love for the festive season and Christmas trees would once again light up the royal households, just as they had done in Albert’s day’. Albert’s passion for Christmas lived on, and the Victorians left us a legacy that we can appreciate today in so many traditions.