Timeless views from the River Nile

Timeless views from the River Nile

Timeless views from the River Nile

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The Nile at Aswan (source)

I have written before of one of my favourite writing spots, the Old Cataract Hotel on the Nile, Egypt. Here, sitting on the marble terrace, I look out at the Nile and watch the traditional boats dreamily float past – feluccas, the romantic wooden gull-winged lateen sail boats used since antiquity.

But it is one thing to sit on the shore and watch vessels travel on these waters, and quite another thing to be aboard such a vessel and see Egypt from the perspective of the river. The views from the water are beyond compare, and they tell the story of this ancient land.

In my novel Song of the Nile, Phares takes Aida sailing on the Nile one evening on his felucca. I write:

Phares had been right: the breeze on the beautiful river shining like glass in the splendid light was stronger than it had seemed from the bank. Filling their sails, it carried them along at a brisk rate, the smooth surface rippled in the wind like the curls of a sheep’s back. The scent of beans in flower was carried to them by a light mist, and Aida inhaled deeply their sweet fragrance. The view slid by, of feluccas dozing with folded sails, lying on their sides like seabirds asleep; endless fields of corn, wheat, beans, cotton and sugarcane stretching afar; and the tiny, unreal villages, their mud walls and winding ways fringed by palms looking like bottlebrushes.

They passed dovecotes taller than the houses: massive earthen domes with niches for nesting, stuck full of posts at the top on which the pigeons could perch or use as supports for their nests. Donkeys grazed on the bank wherever it was clear of reeds, and a caravan of camels kicked up dust as they ambled along a narrow path on the edge of the desert where it bordered the Nile, lined with acacias rising above all other trees. Aida had never noticed before the variety of trees that graced the shores of the river, all of which were native to Egypt. There was the delicate tamarisk, with its bluish-green feathery blooms, the thick-trunked mulberry, with its light-green leaves and edible fruit, the wind-breaking casuarinas, with their long pine needles, the tall eucalyptus, with its camphor-producing pale leaves, and, of course, the sycamore, ‘the tree of love’ of the Ancient Egyptians. This tree they prized above all others, its dense foliage providing welcome shade, while the rosy, plump figs that grew on the trunk in clusters gave their life-prolonging benefits.

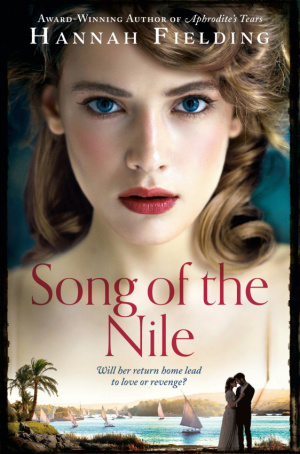

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

There is something timeless about this view, connecting Phares and Aida to their Egyptian ancestors:

Aida returned her gaze fixedly to the passing scenery: a triad of shaggy black buffaloes up to their shoulders in the river and dozing as they stood; a spreading sycamore fig, in the shade of which lay a man and camel asleep; a fallen palm uprooted by the last inundation, its fibrous roots still clinging to the bank, its branches in the water.

As the felucca approached the shores of Luxor, broken pillars of temples were outlined against the horizon. Aida continued to consider the landscape, ever rich in tropic beauty – the sweep of the majestic river, the eternal silence of the sand plains, and the desert hills that lay in the distance. Here, it was impossible to separate the Egypt of the past from the Egypt of today, she mused.

A felucca on the river at Luxor (source)

Later in the story, Phares and Aida travel along the Nile aboard another of Phares’s vessels, his dahabeyeh – a sort of yacht houseboat modelled after the solar boat of the ancient sun god, Ra. I write:

For the next few days, the river stretched endlessly away before them, smooth as glass. The sky was always cloudless, the days warm, the evenings exquisite. Every reach or bend of the river presented objects of delight and historical interest. Aida had started a diary and she spent much time observing and painting with words the vivid images she was seeing and the emotions they aroused in her.

Each morning, they sat on deck, Aida writing letters and her diary; Phares reading medical journals. Now and then, they raised their heads to watch the sunny riverside scenes sliding by at walking pace amid the palm groves, sandbanks, and patches of fuzzy-headed doora, maize, and cotton fields: a boy plodding along the bank between the papyrus and the stones, leading a camel laden with cotton; girls coming to the water’s edge carrying great empty jars on their heads, waiting to fill them when the boat had gone by. Pigeon towers of mud villages peeped through clumps of lebbich trees; a solitary fellah, felt skull-cap on his head and only a slip of scanty tunic fastened about his loins, working a shaduf, stooping and rising again and again, with the regularity of a pendulum. This scene was no different to the paintings Aida had seen in the tombs of Thebes: the man so closely resembled an Ancient Egyptian that she found herself wondering fancifully how he had escaped being mummified four or five thousand years ago.

The Temple of Philae as viewed from the river (source)

On their trip, Aida and Phares visit the monuments between Cairo and Assiout, which are of course inspiring and impressive. But always they return to their boat, and these views that remind them of Egypt’s heritage and traditions.

As if in some languid dream they passed the cool green reaches of Manfalout on the west bank and its picturesque terraced gardens by the waterside; they saw crested minarets and fretted domes, and floated on to where the Arabian Desert again closed in and precipitous mountain crags frowned over the river.

From time to time, a monotonous chant on three notes, which must surely have been heard by the very first Pharaohs themselves, echoed at different places along the shore. Half-naked men on the banks, with torsos of bronze and voices all alike, intoned it in the morning when commencing their labours and continued throughout the day, until the evening brought them repose. Aida loved this song of the water drawers – the song of the shaduf, accompanied by the slow cadences of creaking wet wood. She found the movements of the men manoeuvring it to have a singular beauty: one man would lower the wooden lever to draw water from the river while the next would catch the filled bucket in its ascent, emptying it into a basin made out of the mud of the riverbank.

Rural life on the Nile (source)

I could have filled the entire book with such descriptions, to try to capture something of the essence of my homeland in these views. In our modern, fast-paced world where ‘change’ is so often heralded as necessary and positive, there is something very special about slowing down and seeing the beauty in what is unchanged, a landscape and traditions that have endured. Though we may be on water while seeing these views, I believe they have the power to ground us.