Amelia Edwards: Egyptologist and inspiration

Amelia Edwards: Egyptologist and inspiration

Amelia Edwards: Egyptologist and inspiration

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

I grew up with a very strong female role model: my grandmother, Esther Fanous, was a revolutionary feminist writer in Egypt during the early 1900s and she helped found the Women’s Wafd Central Committee in 1920. It was she who first told me about Amelia Edwards when I was a young girl, and I remember being so awed by the accomplishments of this strong, pioneering English lady.

Amelia Ann Blanford Edwards was born in London in 1831, the daughter of an army officer turned banker. From an early age she was passionate about writing; she published poems and stories during her childhood which she illustrated herself (and she had artistic talent; George Cruikshank, illustrator for Dickens and others, saw her work and offered to become her teacher, but Amelia’s parents saw art as a lowly pursuit).

From her early twenties, Amelia wrote fiction, and she made a name for herself publishing novels that were meticulously researched and written with great care. She is especially remembered for the novels Barbara’s History (1864) and Lord Brackenbury (1880), and the ghost story ‘The Phantom Coach’ (1864).

Amelia’s success as a novelist (Lord Brackenbury was reprinted 15 times to meet demand) meant she had the financial means to pursue her interest in travel. In 1872, she had her first great adventure, taking a trip to Italy with a friend, Lucy, to tour the Dolomites, a region not yet documented and mapped. The bold pair (remember, this was the 1870s and they were women alone) hired mountain guides and explored extensively. The adventure inspired Amelia’s first work on non-fiction, A Midsummer Ramble in the Dolomites (1873).

Back home, Amelia had itchy feet. England, she wrote, felt like a ‘dead-level World of Commonplace’. So, in 1873, she and Lucy travelled to Egypt, and what wonders they beheld, sailing on the Nile from Cairo on a dahabiyeh (houseboat) to Abu Simbel in a group comprising artists, writers and intellectuals.

Amelia poured her impressions of Egypt into A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1877).

In the book, she shared long, evocative descriptions of what she saw. Here is her impression of the island of Philae:

The approach by water is quite the most beautiful. Seen from the level of a small boat, the island, with its palms, its colonnades, its pylons, seems to rise out of the river like a mirage. Piled rocks frame it on either side, and the purple mountains close up the distance. As the boat glides nearer between glistening boulders, those sculptured towers rise higher and even higher against the sky. They show no sign of ruin or age. All looks solid, stately, perfect. One forgets for the moment that anything is changed. If a sound of antique chanting were to be borne along the quiet air–if a procession of white-robed priests bearing aloft the veiled ark of the God, were to come sweeping round between the palms and pylons–we should not think it strange.

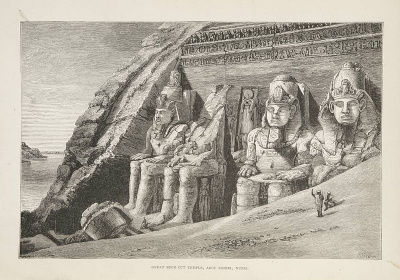

Amelia illustrated the book herself, enabling readers to visualise the extraordinary sights. Here is Amelia’s illustration of the Great Temple at Abu Simbel.

The book was a bestseller and it made a profound difference to how people viewed Egypt, sparking interest in Egyptology.

Following the success of A Thousand Miles up the Nile and her experiences excavating at Abu Simbel, Amelia co-founded the Egypt Excavation Fund in London in 1882. Its purpose was to conduct new excavations and record finds. In 1919, the name was changed to the Egypt Exploration Society (EES), and it is still in operation today.

For the rest of her life, Amelia was devoted to Egyptology. She contributed hundreds of articles on Egypt to publications, and she visited the US for a lecture tour, giving 110 lectures in 16 states. She passionately advocated for the perseveration of ancient monuments against the threats of the modern world.

When she died, in 1892, she bequeathed all of the Egyptian antiquities she had collected, her library and her photographs to University College London (which had been the first college to allow women to study), and she founded the first British professorial chair dedicated to Egyptology, the Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology. The first professor, Flinders Petrie, would train many archaeologists, including Howard Carter of Tutankhamun fame.

Amelia’s grave, at St Mary’s Church, Henbury, Bristol, bears an Egyptian obelisk and a big stone ankh, the symbol for life. She is buried by her partner of 30 years, Ellen Drew Braysher, and her grave is Grade II listed, not only for Amelia’s connections to Egyptology but also for her contribution to LGBT history, for she was open about her love for Ellen. This is the inscription on her grave:

HERE LIES THE BODY OF AMELIA ANN BLANFORD EDWARDS NOVELIST AND ARCHAEOLOGIST BORN IN LONDON ON THE 7TH JUNE 1831 DIED AT WESTON-SUPER-MARE ON THE 1ST APRIL 1892 WHO BY HER WRITINGS AND HER LABOURS ENRICHED THE THOUGHTS AND INTERESTS OF HER TIME

An inspirational woman, and what a legacy she left for us. I will leave you with Amelia’s perfect encapsulation of the wonder of Egyptology, from her lecture Pharaohs, Fellahs and Explorers (1891):

It may be said of some very old places, as of some very old books, that they are destined to be forever new. The nearer we approach them, the more remote they seem: the more we study them, the more we have yet to learn. Time augments rather than diminishes their everlasting novelty; and to our descendants of a thousand years hence it may safely be predicted that they will be even more fascinating than to ourselves. This is true of many ancient lands, but of no place is it so true as of Egypt.