Do Ancient Egyptian artefacts belong in Egypt?

Do Ancient Egyptian artefacts belong in Egypt?

Do Ancient Egyptian artefacts belong in Egypt?

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Egyptian collection at the British Museum

I am an avid collector of Chinese porcelain, Japanese sculptures, French and Italian glass. You will often find me rummaging in flea markets and second-hand shops. The thrill at finding a treasure!

My father was a great collector. He took me on his hunting escapades and to auctions, which I found most exciting. He was a subscriber to the Collectors Guide and Apollo magazines. I spent hours reading about beautiful artworks from around the world.

Of course, these discoveries are treasures for us, but they are not in fact treasures in the sense of their being pieces of great worth, priceless relics of bygone eras; they do not have great historical importance. They are simply objets d’art, precious for their beauty. They are not Ancient Egyptian artefacts, discovered during excavations of tombs and temples.

Song of the Nile opens in a courtroom, where a man, Ayoub El Masri, is standing trial for the theft and illegal possession of Egyptian antiquities. Tragically, the shock of the guilty verdict causes Ayoub to have a heart attack – leaving his grief-stricken daughter, Aida, to vow to clear his name and uncover the plot against him.

Aida knows her father was innocent: Ayoub was a well-known archaeologist, renowned in his field, who had led many excavations and saved numerous Ancient Egyptian artefacts from destruction. She also knows that the smuggling of Egyptian antiquities has grown in Egypt since World War II, a means for poor people to raise money:

‘The excavation of real artefacts happens alongside the work of forgeries. More and more diggers are colonising the western bank. They live rent-free among the tombs, driving donkeys or working in the fields during the day and spending their nights searching for treasure. We are aware that hundreds of families live in this grim way, spoiling the sites of the Ancient Egyptians for their livelihoods.’

Of course, the smuggling also allows rich people to further line their pockets. I write:

‘These antique dealers are getting their hands on stolen antiquities all the time. While foreign Egyptologists are here selling these artefacts for thousands of pounds to their foreign buyers, there will always be looters. They are simply supplying a market.’

Aida’s father’s friend argues:

‘One must understand, these objects have always been taken and sold on… After all, who owns the past? Can we claim ancient artefacts as our cultural property? We ourselves are almost an entirely different culture to our Ancient Egyptian ancestors, are we not?’

To which Aida responds:

‘There are many Egyptians who would fiercely disagree with you… My father certainly would have been hotly opposed to that line of thought. He argued passionately for preserving our antiquities here in Egypt.’

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Where do such antiquities belong? In a museum is the simple answer, safe and preserved for future generations, and open for people to see. The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo has an extensive collection. So, too, do museums abroad, such as the Museo Egizio in Turin.

Sometimes, Egypt has gifted artefacts to other countries. Cleopatra’s Needle is a good example: the obelisk, built in the city of Heliopolis in c. 1450 BC, now stands on Victoria Embankment, London. It was a gift from Sudan Muhammad Ali, ruler of Egypt from 1805 to 1848.

Cleopatra’s Needle

Sometimes, though, the possession of Egyptian artefacts by foreign countries is a source of contention. Recovering the artefacts can be a matter of watching for their trade; in January 2019, for example, a stone tablet of King Amenhotep was auctioned, and the British authorities worked with the Egyptian Embassy in London to save the artefact.

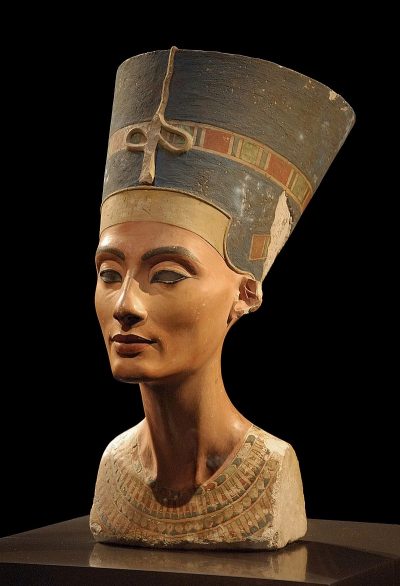

Often, though, it is museums which are holding treasures of Egypt. Recently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art returned the gold coffin of Nedjemankh, dating to the first century B.C., after it was found to have been stolen from Egypt through the use of forged papers. Not all issues are resolved in this way, though. The hugely important Rosetta Stone, from which we unlocked the mystery of hieroglyphs, remains at the British Museum, London, and the bust of Queen Nefertiti, which dates back 3,300 years, is part of the collection of the Museum of Berlin.

Bust of Queen Nefertiti

Whether or not these artefacts were obtained illegally, and not smuggled or exported through the use of forged papers, they remain a source of contention.

What do you think? Do all Egyptian antiquities belong in their country of origin? Ought foreign museums and collectors return them, or at least return the most precious artefacts, like the Rosetta Stone and the Nefertiti bust? Or is such change unrealistic – is it a good thing that museums worldwide are able to give visitors a glimpse into Ancient Egypt?

Photo credits: 1) Jaroslav Moravcik/Shutterstock.com; 2) Ethan Doyle White/Wikipedia; 3) Philip Pikart/Wikipedia.

I was first reminded of the ethics of buying artifacts in 1973 at the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul. I first visited Istanbul two years earlier. I bought a small vial purported to be from 2500 BC. My wife’s uncle was a glass collector. He told me he thought it was genuine. I saw an almost identical in a museum in Chania, Crete. I also saw a photograph of one in a Bible Dictionary that gave the same date. In 1973 I went back to the same location in the Bazaar. It was then a rug shop. I asked the owner… Read more »

Goodness, so it was a genuine artefact? Sadly, thievery has been rife, because these artefacts have such value.

I believe all artifacts should go back to Egypt. Visitors should only see them in Egyptian museums.

There’s certainly a very strong argument for this. Imagine how exciting a trip to Egypt would be!