Egyptomania and its influence on Western architecture

Egyptomania and its influence on Western architecture

Egyptomania and its influence on Western architecture

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The Luxor Hotel, Las Vegas

Egyptomania is a word derived from the Greek Egypto, meaning Egypt, and mania, meaning madness; essentially, it means a great enthusiasm for all things relating to Ancient Egypt.

It was the French who sparked Egyptomania in the West, with Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign (1798–1801). Hundreds of French scholars, scientists and artists visited Egypt and documented the monuments they found there in the Description de l’Égypte (Description of Egypt). The knowledge this series of publications imparted was immense and revelatory for people.

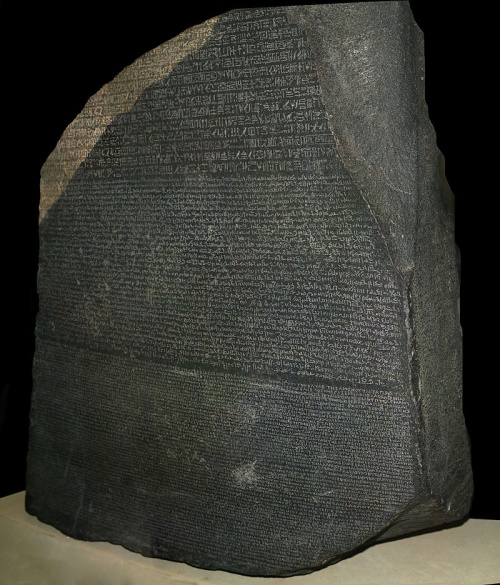

One of the discoveries made on the campaign was the Rosetta Stone, a stele dating back to the Hellenistic period that’s inscribed with a decree in Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and demotic (a cursive form of hieroglyphics), and in Ancient Greek. The British, having defeated the French, took the stone to London and put it on display at the British Museum (where it has remained since), and it stirred great excitement amongst scholars for it offered a key for translating the Ancient Egyptian scripts. Scholars worked furiously on the puzzle for decades, and finally, in 1826, Jean-Francois Champollion published the first dictionary of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, and at last the mysteries of the ancient civilisation could be unlocked.

The Rosetta Stone

This was the dawn of Egyptology – the academic study of Ancient Egypt, encompassing its culture, history, language, religion and architecture; and it was the dawn of Egyptomania. People were learning so much about this ancient civilisation, its temples and tombs, its deities and kings, its customs and religion, and they were fascinated and hungry for more. As historian Manon Schutz writes, ‘[Egyptomania] became representative of exoticism, romance, and mysticism’.

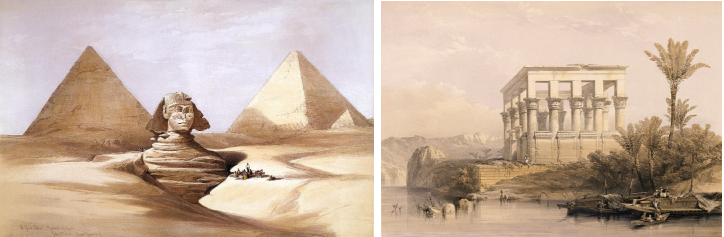

Few people could visit the faraway land of Egypt, but they could experience a little of its heritage through the arts at home. They could watch Verdi’s opera Aida, the tragic love story of a slave girl and an army general. They could read poems like ‘Ozymandias’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley, about a statue of the pharaoh Ramesses, lost to time. They could see paintings and lithographs depicting scenes from Egypt, like those by Scottish artist David Roberts.

‘The Great Sphinx (and) Pyramids of Gizeh (Giza)’ and ‘The Hypaethral Temple at Philae called the Bed of Pharaoh’ by David Roberts

Egyptomania was also very inspiring for architects. Impressed by the Egyptians’ extensive customs around death, they began to draw on Egyptian icons in the design of tombs and cemeteries. In Highgate Cemetery, London, an Egyptian Avenue was built, incorporating a grand gateway flanked by obelisks. Across Britain, wealthy people commissioned mausoleums in the shape of pyramids.

Earl of Buckingham’s tomb, Blickling Hall, Norfolk

Obelisks became popular. Some, like Cleopatra’s Needle on the Thames in London, were taken from Egypt, but many were built too; the Washington Monument in the US is a famous example.

Obelisk at Castle Howard, North Yorkshire

Egyptian influence was seen in statues, in fountains, in gateways, in columns – in all aspects of architecture.

Sphinxes in the Fontaine du Palmier, Paris

In 1812, antiquarian William Bullock built a museum in Piccadilly, London, in which to display his Egyptian collection, and he gave his architect free reign to make it look Egyptian. The resulting ‘Egyptian Hall’ was the first building in England to follow the Egyptian style, which came to be called Egyptian Revival architecture.

The Egyptian Hall

In the 1920s, the thrilling discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter fuelled a new wave of Egyptomania, and this fed into the development of the Art Deco style. Art Deco drew on motifs from Egyptian art like obelisks, hieroglyphs, the Sphinx and the Pyramids.

The iconic elevator doors of the Chrysler Building, New York, featuring an Egypt-inspired lotus pattern

Since the beginning of Egyptomania, Egypt-inspired architecture has proved popular in the West, and to this day we can see the influence of Egyptomania in architecture in everything from tiny details up to the entire design vision.

The Pyramid at the Louvre, Paris

If, like me, you are intrigued by how a passion for Ancient Egypt has influenced architecture, you may enjoy a free online talk this evening hosted by the British Museum: ‘Egyptomania and the influence of ancient Egypt on art and architecture in the 20th and 21st centuries’. The speakers are Dr Benjamin Hinson, Egyptologist and curator at the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum; Dr Anna Ferrari, curator at the Science Museum; Dr Chris Elliott, author; and Dan Cruickshank, art historian and BBC television presenter. You can find out more and book your place on the British Museum’s website.

Picture credits: 1) Philip Bird/Shutterstock; 2) Hans Hillewaert/Wikipedia; 3) public domain/Wikipedia; 4) Northmetpit/Wikipedia; 5) Kev Gregory/Shutterstock; 6) Volodymyr Dvornyk/Shutterstock; 7) public domain/Wikipedia; 8) Tony Hisgett/Wikipedia; 9) Benh Lieu Song/Wikipedia; 10) British Museum.