The Temple of Hathor at Dendera

The Temple of Hathor at Dendera

The Temple of Hathor at Dendera

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The Ancient Greeks had Aphrodite, the Romans had Venus, but the original goddess of love was Hathor of Ancient Egypt. Like her counterparts, Hathor was the very epitome of beauty and love. Thus when, in Song of the Nile, Phares comments on a painting of the goddess and likens Aida’s profile to that of Hathor, it is a signal of his deep feelings for her.

While taking a cruise together on the Nile, the couple agree that it would be remiss of them to pass by Dendera without stopping and visiting the Temple of Hathor. They arrive at Dendera in the early morning, and here is how they first perceive the ancient site:

They came to a plain, green and level as a lake, widening out to the foot of the mountains – and the temple, islanded in that sea of rippling emerald, rose up before them upon its platform of stone and blackened mounds of earth. Although they were still far off, it looked enormous, a sharply defined mass of dead-white masonry. The walls sloped in slightly towards the top and the façade appeared to be supported on six massive columns, with the remnants of a large stone doorway still standing in the centre of the courtyard leading to the main temple building.

‘It looks very naked and solemn,’ Aida remarked. ‘More like a tomb than a temple.’

‘That’s because we’re too far away to distinguish any of the carvings or images of legends on the walls,’ Phares answered, squinting into the distance. ‘I’ve visited this temple before, and trust me, the paintings are remarkable and so well preserved.’

As they drew nearer and the ground rose, the details of the temple gradually became more distinct. It was surrounded by a hefty mud brick enclosure. Inside the boundary, rows of ruined walls showed the original position of the ancient streets and what was once their buildings.

And now they were close enough for Aida to see that the huge, round columns of the façade were topped with stone-headed Hathor capitals, the rays of the sun seeming to light a spark of life in their carved eyes and accentuate the melancholy smile that gives most Egyptian statues such a mysterious attraction. And the walls, instead of being smooth and tomb-like, were covered with a multitude of sculpted figures.

My descriptions of Dendera are based on my own visit there years ago, when I was struck by how well preserved the site is and by its quiet solemnity.

A temple has existed on the site since the Middle Kingdom (c. 2030–1650 BC), but the structures we see today largely date from the reign of Ptolemy XII Auletes (c. 80–58 BC) and Cleopatra VII (69–30 BC) through to the reign of the Roman Emperor Trajan (98 to 117 AD).

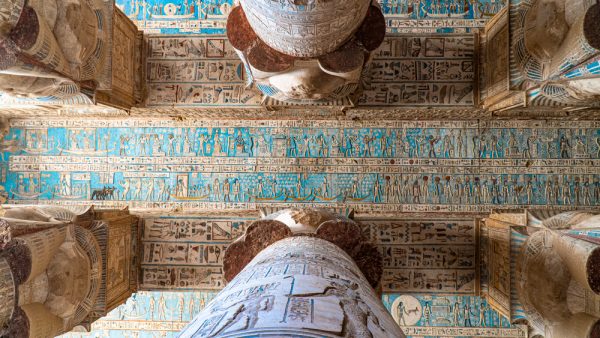

The Temple of Hathor contains various crypts and halls, including the small and large Hypostyle Halls, and shrines to numerous gods, from Isis to Ra and of course Hathor. It is one of the best-preserved Ancient Egyptian sties, and one of the few temples to have survived with its roof intact, and thus also its ceilings. The ceilings at Hathor have been carefully cleaned (of the soot from centuries of Bedouins’ fires), and the results are spectacular.

Restored ceiling in the temple

One Hathor ceiling relief is especially famous: the so-named Dendera zodiac, found in the sanctuary for Osiris, which depicts the night sky in ancient times. It is currently on display at the Louvre, Paris.

The Dendera zodiac

The artworks in the Temple of Hathor are so detailed and vivid, it’s like they were created only yesterday. One could spend hours taking in all of the murals and reliefs depicting so many deities and kings – and, notably, a famous queen, Cleopatra, with her son by Julius Caesar, Ptolemy XV (Caesarion).

Reliefs of Cleopatra and Caesarion

You can also see the ‘Dendera light’, a stone relief in which the god Horus, in the form of a snake, is shown rising from a lotus flower through the womb of Nut, goddess of the sky and heavens. (The relief has become somewhat famous because some have argued it resembles a modern-day electrical lighting device.)

The Dendera light

Two staircases in the temple lead up to the roof; these were used for a ritual in which a statue representing Hathor was taken to the rooftop for sunrise so that she would merge with the sun. When I visited the temple, it was possible still to climb up to the roof level, and the view from there was simply stunning.

I will leave you with this extract from Song of the Nile, which I hope conveys to you the unique and romantic feeling of this ancient place.

Phares held her hand. ‘Come, let’s climb up the staircase to the roof. You’ll see how intricately the zodiac has been carved into the ceiling.’

The effect of the portico as Aida stood at the top of the staircase was one of overwhelming majesty. Hieroglyphs, emblems, strange forms of kings and gods covered every foot of wall space, frieze and pillar. Images of the sky goddess, Nut, swallowing Ra, the sun god, at dusk to birth him back to the world at dawn were spread out all along the walls.

Phares gestured towards one of the paintings, his mouth curving with amusement. ‘I can tell you, the god Amon himself, the procreator, is often crudely drawn, but even he would seem chaste compared with the hosts of this temple.’

The beautiful goddess Hathor – her throat, her hips, her unveiled nakedness – was portrayed with a searching and lingering realism; her flesh seemed almost to quiver. She and her handsome spouse contemplated each other naked, their laughing eyes seemingly alive and intoxicated with love.

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Photo credits: 1) Abrilla/Shutterstock.com; 2) Merlin74/Shutterstock.com; 3) public domain/Wikipedia; 4) Alex Lbh/Wikipedia; 5) Olaf Tausch/Wikipedia.