Muse: The woman in the shadows

Muse: The woman in the shadows

Muse: The woman in the shadows

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Galarina Dali, Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar, Victorine Meurent, Camille Claudel, Joanna Hiffernan, Alma Mahler… very influential and inspiring women, but do you know of them? Perhaps, or perhaps not. Certainly, though, you know well the names of the men with whom these women are paired (so well that I need not write their surnames): respectively Dali, Picasso, Manet, Rodin, Whistler, Klimt.

The tradition of the female muse in art dates back to ancient mythology. To the Greeks, the muses were Zeus’s daughters, goddesses dedicated to the arts and knowledge. In Roman mythology, they were named Calliope for epic poetry, Clio for history, Euterpe for flutes and lyric poetry, Thalia for comedy and pastoral poetry, Melpomene for tragedy, Terpsichore for dance, Erato for love poetry, Polyhymnia for sacred poetry and Urania for astronomy. For many centuries since, artists have turned to real-life muses for inspiration.

Galarina Dali, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Victorine Meurent, Camille Claudel, Joanna Hiffernan, Alma Mahler… these muses are known, if not anywhere near as well-known as the artists who were inspired by them. Most often, the muse is a woman in the shadows.

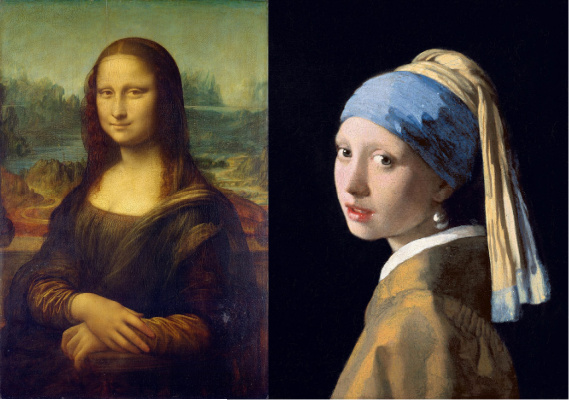

The Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci is a famous example of a painting whose subject was not declared by the artist, and for 500 years art historians have endeavoured to name the muse (current thinking is that she was Lisa Gherardini). The Girl with the Pearl Earring is Vermeer’s most famous work, and yet to this day Vermeer’s muse is unknown.

I have always been fascinated by muses, and especially the ones in the shadows. In my novel Masquerade, the heroine, Luz, is writing a biography of a famous Spanish artist, and when she uncovers references to his having a muse, La Pouliche, she is intrigued.

Luz searched Andrés’s face, trying to read his features. Suddenly she sensed that he resented her questions. But how was she supposed to write about his uncle if she couldn’t get to grips with her subject? La Pouliche – it was her official name – contrary to all the information she had gathered so far, had clearly been a great part of the artist’s inspiration.

Luz continued to walk around the room, examining each and every one of the numerous small standing and reclining figures of La Pouliche, the Filly. Always in a relaxed attitude, the beautiful body of Eduardo’s muse knelt, stood, or reclined, arms draped about her head, each part of her alive and sensually provocative. Luz paused in front of one of the bronze busts of the model whose head was thrown back in an arrogant taunt, her mane of hair cascading untidily behind her. She could almost see the fire seething in the large, animated eyes. Where had she seen that look before?

Masquerade: available to buy from my shop

Thus in Masquerade, Luz wishes to shine a light on the woman in the shadows. In my novel Concerto, however, the situation is more complex, for the heroine finds herself cast in the role of muse. On their first date, Umberto is so moved by her that he composes a piano piece on the spot, ‘Songe d’une Nuit d’Amour,’ and he tells Catriona that it was she who created it, for she is ‘an infinitely powerful muse’.

A decade later, Umberto has lost his sight and his will to compose; but when Catriona comes to his Lake Como home to work with him as a music therapist, he is still a believer in the power of the muse. The following extract is taken from a scene in which Umberto and Catriona sail across the lake to Isola Comacina:

‘Didn’t Bellini have a villa here too?’ she asked.

‘Further down the shore, near Moltrasio: the Villa Passalacqua, a beautiful place… Back in the 1820s, Bellini’s favourite diva was Giuditta Pasta, who had her own villa just across the lake from his. Legend has it that he could hear her voice echoing over the water and it helped him compose. She was his muse, as you are mine, mia bellisima fidanzata.’

Catriona is not convinced. She feels that thinking he needs a muse could be holding Umberto back from playing and composing. I write:

She didn’t believe in muses; she believed in hard work and application.

Catriona is determined to coax Umberto back to the piano stool; in fact, she’s quite prepared to get tough with him, telling him he must set aside his self-pity and arrogance. Of course, she is right: Umberto must stop wallowing and return to his passion. But what Catriona fails to see is that music is not his only passion in life; it was his passion for her all those years ago that inspired ‘Songe d’une Nuit d’Amour’.

Concerto: available to buy from my shop

Cast aside by Umberto as a young woman, Catriona has been hurt profoundly. To be Umberto’s muse once more, to give her heart to him and inspire his music and his courage, to be the woman behind the great works he will write… that’s a lot to take on. After all, she had to sacrifice her own dream of becoming an opera singer due to their liaison in her teens. Will she give this much of herself to Umberto? Will doing so mean losing herself, being in Umberto’s shadow?

Or, is it incredibly valuable to step into the role of muse? Is the muse as important to the creative work as the artist’s talent? Will the music Catriona inspires in Umberto, the new music he creates, bring them both out of the shadows, in a sense, and into the light?