Source of life: the mighty Nile of Egypt

Source of life: the mighty Nile of Egypt

Source of life: the mighty Nile of Egypt

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The longest river in the world, extending some 6,700 kilometres, the Nile runs south from eastern Africa all the way to the Mediterranean. (Upper Egypt is southern Egypt, so called because it is closest to the source of the Nile, and Lower Egypt is the northern part.)

Take a look at a map of Egypt and at once the significance of the Nile becomes apparent. The vast majority of Egyptian territory is desert, and most settlements are along the Nile Valley and the Delta.

The Nile Valley refers to the fertile land surrounding the river: it regularly floods, and when the floodwaters recede, the black silt that is left behind fertilises the soil (ancient Egyptians called the country Kemet, which translates to ‘the black land’). In this way for thousands of years the Nile has made the surrounding land fertile for agriculture. Crops like wheat, flax and papyrus were traded, helping the country to build economic stability.

Naturally, settlements sprang up along the length of the river for the people who worked the land. Historically, though, the flooding could be very dangerous, sometimes sweeping away people and homes. In the time of the pharaohs, monitoring stations were set up to watch for floods and warn those downstream; in modern times, the river is controlled by dams.

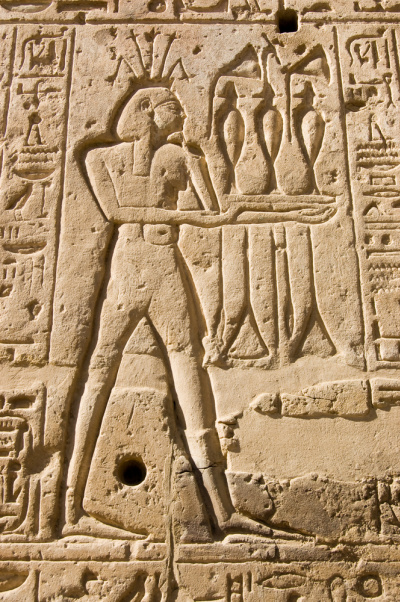

Despite the downside of the flooding, Egyptian people have always been very grateful for the Nile, for as the Greek historian Herodotus put it, ‘Egypt was the gift of the Nile.’ Ancient Egyptians worshipped Hapi, the god of the annual floods. They believed the Nile was the path from life to the afterlife (they built all their tombs on the west side of the Nile, because they believed this was the direction of death, since the sun god, Ra, died in the west each evening).

Stone carving of Hapi in the Temple of Seti I, Luxor.

To this day, the Nile is the heart of life in Egypt, a timeless certainty, reassuringly unbothered by progress and conflict and upheaval. As I write in Song of the Nile:

The Nile, the patriarch of rivers, lay silver and serene. Centuries had come and gone and there he was, the ‘Father of All Life’, flowing gently in the sweltering darkness, suffering no change that seemed of any account.

In the novel, Aria’s house overlooks the Nile. This is the view from the drawing room:

From here the view was breathtaking: the slow-moving Nile lying like a pearlescent sheet, so still it seemed as though you could walk across the water to the farthest bank, where the pink hills of the Valley of the Tombs rose up, changing colour as the sun rode the sky. During the day, feluccas, the romantic gull-winged sailing boats used since antiquity, skimmed over the surface of the river like big white moths.

Beyond sitting on the banks of the Nile and drinking in the views, a slow, languid boat ride – on a felucca or perhaps a luxurious dahabiyya (meaning ‘golden boat’) – will reveal to you scenes of astonishing natural beauty. The stretch of river from Luxor to Aswan is especially beautiful, taking you past amazing architecture and historic moments.

Ultimately, to get close to the Nile is to feel connected to life, then and now. As the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote, the Nile is ‘forever new and old’, a ‘mighty, mystic stream’.