Remembering the fallen on Poppy Day

Remembering the fallen on Poppy Day

Remembering the fallen on Poppy Day

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

My latest novel, Song of the Nile, is set in Egypt just after the Second World War. The heroine, Aida, was a nurse in England during the war years, nursing both soldiers and victims of the Blitz. The world, I write, had been ravaged by war, and on a daily basis Aida witnessed suffering that would change her irrevocably – make her tougher, yes, and more resilient in a sense, but wound her too; make the world a darker place.

It was hard to write of this time. Not fiction in any sense, but fact for everyone who lived during those years. People dying, people terrified, people despairing – people suffering. But I did not shy away from writing of the war, just as we should not shy away of remembering, ‘Lest We Forget’.*

Today in the United Kingdom and across the Commonwealth, we fall silent at 11 a.m. – just as the guns did more than 100 years ago. It was at that time, on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, that the hostilities of the First World War ended, with the armistice that had been signed that morning coming into effect.

The two-minute silence was made tradition the year after the war. An article in the Manchester Guardian on 12 November 1919 described that first silence in London:

The first stroke of eleven produced a magical effect.

The tram cars glided into stillness, motors ceased to cough and fume, and stopped dead, and the mighty-limbed dray horses hunched back upon their loads and stopped also, seeming to do it of their own volition.

Someone took off his hat, and with a nervous hesitancy the rest of the men bowed their heads also. Here and there an old soldier could be detected slipping unconsciously into the posture of ‘attention’. An elderly woman, not far away, wiped her eyes, and the man beside her looked white and stern. Everyone stood very still … The hush deepened. It had spread over the whole city and become so pronounced as to impress one with a sense of audibility. It was a silence which was almost pain … And the spirit of memory brooded over it all. (source)

To this day, the silence is a deeply moving and profoundly meaningful way to remember those who gave their lives in order that we may live in peace.

We remember not only with silent reflection and prayer; we remember with poppies. In Ancient Egypt, the poppy was a symbol of Osiris – god of death and the resurrection into eternal life. Nowhere has that symbol had more meaning than on the First World War battlefields at Ypres.

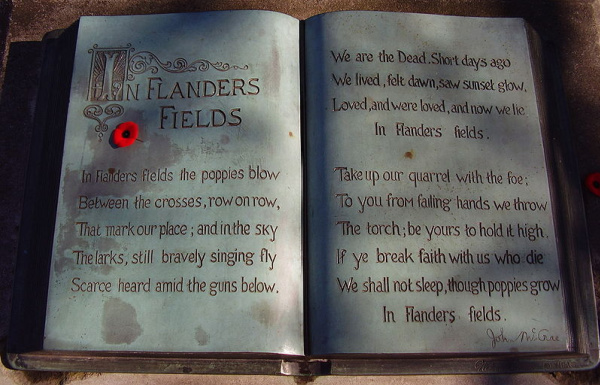

On 3 May 1915, a major of the Canadian Field Artillery named John McCrae composed a poem. He called it ‘In Flanders Fields’.

In Flanders Fields, the poppies grow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

McCrae, a medical officer, had been treating the wounded from the Second Battle of Ypres. To his despair, he was unable to save so many men, including one of his friends. At his friend’s burial service, McCrae looked around and noticed how quickly poppies grew up around the graves. This was his inspiration for ‘In Flanders Fields’, which, once published, became hugely popular as a source of solace and strength.

John McCrae memorial, Guelph, Ontario

It was an American professor, Moina Michael, who conceived the idea of wearing a poppy as a symbol of remembrance. Inspired by ‘In Flanders Fields’, she wrote the following poem in 1918.

We Shall Keep the Faith

Oh! you who sleep in Flanders Fields,

Sleep sweet – to rise anew!

We caught the torch you threw

And holding high, we keep the Faith

With All who died.We cherish, too, the Poppy red

That grows on fields where valor led;

It seems to signal to the skies

That blood of heroes never dies,

But lends a lustre to the red

Of the flower that blooms above the dead

In Flanders Fields.And now the Torch and Poppy Red

We wear in honor of our dead.

Fear not that ye have died for naught;

We’ll teach the lesson that ye wrought

In Flanders Fields.

The powerful symbolism of the poppy: it never ceases to inspire.

In 2014, I took a train to London to visit the Tower of London; specifically, the public art installation Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red.** To commemorate the outbreak of the First World War, 888,246 ceramic poppies were arranged in a flowing, rippling sea.

I will never forget how I felt as I looked at all those poppies, one for each British or Colonial serviceman who died in the war. So many poppies – and across the world, so many more seas we could create in remembrance.

We will never forget.

* Famously used in war memorials, this phrase is a quotation from a poem entitled ‘Recessional’ by Rudyard Kipling, composed for the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1897.

** A quotation from a poem by an unknown English soldier in World War I: ‘The blood swept lands and seas of red, / Where angels dare to tread’.

Photo credits: 1) Sergii Votit/Shutterstock.com; 2) Lx 121/Wikipedia; 3) P Gregory/Shutterstock.com.