The repatriation of artefacts

The repatriation of artefacts

The repatriation of artefacts

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Part of the Elgin Marbles frieze at the British Museum

Recently, the Elgin Marbles have been in the news once again, as the question of their proper ownership is debated. These sculptures, also known as the Parthenon Marbles, are from Ancient Greek: they were part of the Parthenon in the Acropolis of Athens and date to the 5th century BC. They are not, however, to be found in the Acropolis Museum of Athens; they are on display at the British Museum, London, having been taken from Greece by the 7th Earl of Elgin in the early 19th century and sold to the government.

For almost 200 years, Greece has been calling for the Elgin Marbles to be returned and reunited with the rest of the Parthenon frieze. The British government, though, has refused to do so.

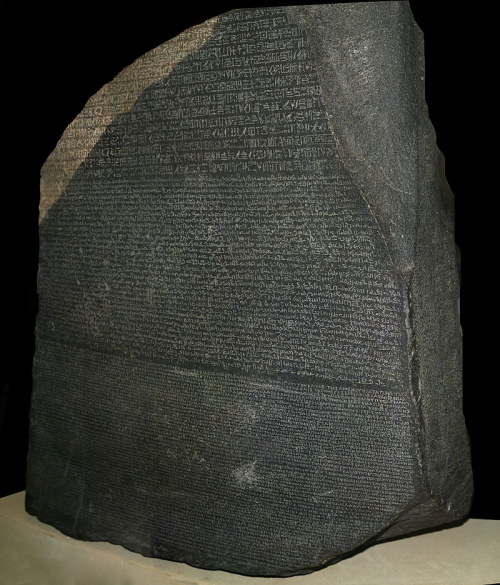

The Elgin Marbles are far from the only artefacts whose ownership is hotly debated. Another such artefact is also found in the British Museum: the Rosetta Stone. This stele is an immensely important Egyptian artefact, having allowed Jean-François Champollion, in 1832, to decipher hieroglyphics and thus enable Egyptologists to unlock the secrets of the Ancient Egyptians.

The Rosetta Stone

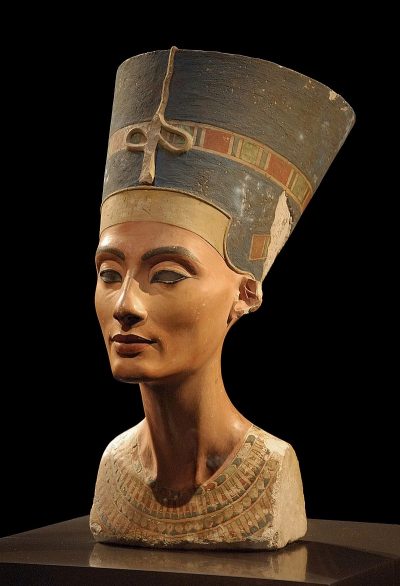

It was soldiers of Napoleon who first found the stone, and when the British defeated the French in Egypt in 1801 they took the stone back to England, where it has been on display at the museum since 1802. Since the early 2000s, Egypt has requested the return of this precious artefact – along with other important ones, like the bust of Nefertiti in the Neues Museum, Berlin and the Dendera Temple Zodiac in the Louvre, Paris.

Bust of Nefertiti

The Dendera zodiac

What are the arguments in favour of repatriation of artefacts like the Elgin Marbles and the Rosetta Stone? Well, of course there is the significant cultural value of a country owning artefacts from its own heritage, of bringing them home. There is also the issue of whether the artefact in question was obtained legally or was ‘looted’ by colonialists. In the case of the Elgin Marbles, for example, Elgin was adamant that he had been given permission to take the marbles by the government ruling Greece at the time, and yet some of his contemporaries did not see the acquisition as valid. In his poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, the peer and poet Lord Byron wrote:

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne’er to be restored.

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch’d thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

According to the BBC, a recent poll of British people found that 16 per cent believe the Marbles should remain in Britain, while 54 per cent think they should be returned to Greece. Former culture minister Lord Vaizey is heading a new advisory body whose aim is to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece – and yet to do so would mean changing British law, and the government is opposed to this.

Why oppose the repatriation of precious artefacts? It largely comes down to taking the view that many museums have a broad remit to help us learn about world history – not just the history of our own country. If you repatriated all artefacts to their country of origin, a museum would be narrow in focus, and learning about other cultures and peoples would be out of reach for all but those who can travel widely.

In 2002, a joint statement was issued by leading museums around the world, including the ‘Big Five’: the British Museum, London; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Louvre, Paris; the Hermitage, Saint Petersburg; and the State museums of Berlin. In their ‘Declaration on the importance and value of universal museums’, they wrote:

[W]e should acknowledge that museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation. Museums are agents in the development of culture, whose mission is to foster knowledge by a continuous process of reinterpretation. Each object contributes to that process. To narrow the focus of museums whose collections are diverse and multi-faceted would therefore be a disservice to all visitors.

The Elgin Marbles at the British Museum attract 6 million visitors per year

Some also argue that artefacts that have been in a country for a long time become part of the cultural heritage of that country. The poet Keats, for example, visited the British Museum, saw the Elgin Marbles, and was inspired to write his poem ‘On Seeing the Elgin Marbles’.

There is also the argument that ancient relics like the Elgin Marbles and the Rosetta Stone are not Greek or Egyptian, but belong to us all. On the subject of the Elgin Marbles, the Trustees of the British Museum stated:

[T]he sculptures are part of everyone’s shared heritage and transcend cultural boundaries. The Trustees remain convinced that the current division allows different and complementary stories to be told about the surviving sculptures, highlighting their significance for world culture and affirming the universal legacy of ancient Greece.

On both sides of the debate people argue with great passion, for the artefacts in question are of such historical and cultural significance.

What is your opinion on repatriating artefacts? I would love to hear your thoughts.

Picture credits: 1) Mark Higgins/Shutterstock; 2) Hans Hillewaert/Wikipedia; 3) Philip Pikart/Wikipedia; 4) public domain/Wikipedia; 5) Nicolas Economou/Shutterstock.