Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo

Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo

Shepheard’s Hotel, Cairo

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

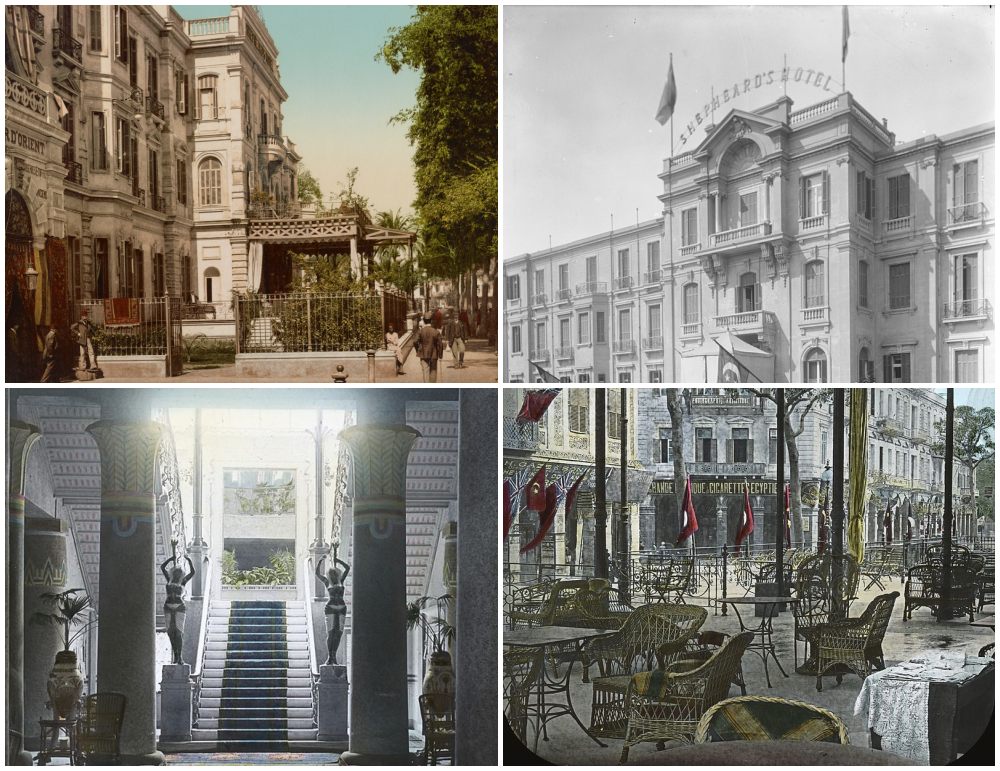

For Aida in Song of the Nile, a visit to Cairo of course means a stay at the famous Shepheard’s Hotel. In the 1940s, there was no finer hotel, a place synonymous with luxury and opulence.

The hotel was established in 1841 by an Englishman, Samuel Shepheard (originally, it was named Hotel des Anglais, meaning English Hotel). For more than a century it was the place to stay and socialise in Egypt, and it was particularly popular with politicians and officers of the military. Notable guests included Aga Khan, the Maharajah of Jodhpur, Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener and Theodore Roosevelt.

Here’s a glimpse of the exterior of the hotel as seen through Aida’s eyes as she arrives in Song of the Nile:

The car stopped in front of a prestigious three-storey building whose relatively sober façade was set back from the pavement and fronted by a broad set of steps flanked by two dwarf palm trees planted in giant decorated stone pots. The steps led up to the famous Shepheard’s Hotel terrace and beyond that, to its entrance lit by wrought-iron wall lamps. These were both sheltered under an intricate mushrabeya canopy set on narrow columns that, during the daytime, protected visitors from the sun and were guarded by a pair of small stone sphinxes taken from the Temple of Serapis at Memphis. The terrace, tiled with Moorish blue, green and orange motifs, was enclosed by a finely chiselled wrought-iron balustrade and set with rattan chairs and tables. In an elevated position, two metres above street level, it commanded a shaded view of the picturesque ceaseless stream of comings and goings along Sharaa Ibrahim Pasha, Ibrahim Pasha Street, below.

Inside is just as impressive:

The interior was true to its reputation of opulence, and more. It was done up in the pharaonic style, with the thick lotus-topped alabaster pillars in the main hall a copy from the ones at the Temple of Karnak in Luxor. The lobby was furnished with rattan chairs, the walls adorned with paintings and sketches of Ancient Egypt and there were beautiful ornate hourglass urns containing dwarf palms set here and there on small, delicate marble tables. A pair of tall, ebony caryatid light-bearers, in the image of topless pharaonic women with golden headdresses, stood like mute sentinels on low columns each side of the elegant double staircase that wound itself gracefully to the upper floors.

Aida has a meal with her friend in the grand dining room at the hotel, which is a study in elegance:

The high-ceilinged Moorish dining room at Shepheard’s, like the rest of the hotel, was magnificent and was packed for lunch. The maitre d’hôtel greeted Aida and Camelia at the door and showed them to one of the last empty tables. The elegant room was cool, dimly lit by different-sized Mamluk copper lanterns suspended from keyhole arches. The walls were adorned with tadelakt plaster, zellige tiles, motifs carved in the top of the marble columns and leaf and flower designs. Suffraggis, each clad in a white kaftan with red cummerbund, red fez and slippers, glided effortlessly around the tables, appetising dishes of food balanced on their outstretched hands. At the far end of the crowded room, on one side, stood a beautiful six-panelled mashrabiya arabesque screen, while nearby, a three-tier stone fountain, its cooling blocks of ice ringed by beautiful banked-up plants and flowers, cooed monotonously in the background.

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Shepheard’s was famous at the time for its ‘long bar’, so called because the bar was always so busy, it took a long time to be served. (During the Second World War, Rommel apparently said, ‘I’ll be drinking champagne in the master suite at Shepheard’s soon,’ referring to his plan to take Cairo; people would joke that the long bar would hold him up.) In Song of the Nile, Aida doesn’t drink in the bar, but she does attend a fashion show in the ballroom, which would be lavishly decorated for events:

Every New Year’s Eve the ballroom of the glamorous Shepheard’s Hotel would be converted into the Garden of Eden, a Chinese pagoda or any other scene that took the fancy of the management. Tonight, the sumptuous colonnaded ballroom was decorated with a coloured palette of blue and gold, reflecting the desert’s natural beauty. Displays of waving palm trees and waxwork figures of camels and sultry Bedouins adorned various parts of the magnificent high-ceilinged room in which the blue lighting was designed to mirror a desert night sky illuminated by the moon and stars. Beneath it, the catwalk dividing the room in two was covered in a shimmering, almost translucent sheet of marble to represent the Nile. As if on its riverbanks, at tables and chairs on either side the prince’s dazzling guests were seated, who had come to view the exciting 1946 avant-garde styles the Parisian couturiers had brought to Cairo for the haut monde’s delectation.

Sadly, the hotel was destroyed in 1952 during the Cairo Fire, in the lead-up to the Egyptian Revolution. But it will always be remembered as a place of wonderful glamour and grandeur, an important part of Cairo’s history.