A caged bird? The place of a woman in 1940s Egypt

A caged bird? The place of a woman in 1940s Egypt

A caged bird? The place of a woman in 1940s Egypt

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Luxor, Egypt, 1946. Twenty-six-year-old Aida El Masri returns to her family’s estate in Egypt. For the past eight years she has lived in England, where she worked as a nurse helping those wounded during the war. There, she was respected as a professional, and she enjoyed the same social freedoms as the other young women with whom she worked. She was free to do as she liked with her time, to befriend whoever she liked, date whoever she liked (though she was too busy with her career to do so). Aida found it easy to get in touch with her English side – for her mother was English – and fit into this society where women were making great strides towards independence.

Returning to Egypt from this fast-evolving world is a shock for Aida. I write:

Coming back to Luxor, Aida knew that she would have to navigate the conservative values of Egyptian society with some self-restraint. Egypt had remained in its own cocoon during the war and its society had failed to be touched by any form of sexual liberation, even in upper-class circles. It had been so different in wartime England. There, Aida had experienced the kind of social freedom in which her independent nature revelled. Suddenly she felt very isolated and alone in this place where she used to belong.

Here, a woman has precious few rights. By her age, it is expected that Aida would have married and had a string of children; as Phares tells her, ‘You’re at an age when every sensible woman should be married, have a home, a husband and children.’

Being a good Egyptian wife means deferring to your husband. A woman cannot even leave the country without the permission of her husband or father.

It strikes Aida that men think they have the right to rule women. A woman who thinks for herself? Dangerous. A woman who drives? Madness: ‘Girls aren’t meant for wheels,’ Aida is told, ‘they should stay on their feet.’ A woman who dares to explore, to spread her wings? ‘Adventurousness is not a good trait in a woman,’ her uncle tells her. And should Aida probe for answers as to how her father came to be framed for a crime he did not commit, she is warned that ‘people will not approve of a woman digging around’.

Continually, Aida is told that she needs a man to protect her. Even staying alone in a hotel in Cairo is considered risqué. I write: ‘A woman alone in Egyptian society was a vulnerable target of gossip and opinion, especially one like Aida with her English sense of entitlement to freedom.’

What of the estate that Aida has inherited from her father? It seems ludicrous to men like family friend Naguib that Aida could possibly manage the estate herself. ‘It is much too heavy a burden for a woman alone to bear,’ Naguib tells her, ‘and that is where you would benefit from marrying Phares Pharaony.’ It is expected that Aida will marry her neighbour and hand over her land to her husband like a good little Egyptian wife. This is an expectation that does not sit well with Aida!

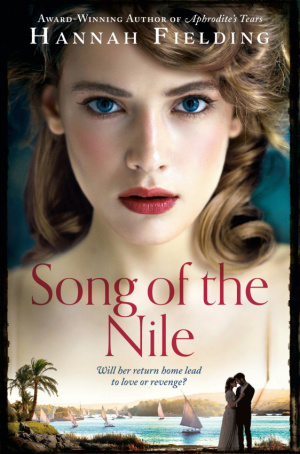

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Aida loves Egypt; her father was Egyptian, she grew up here, the land is in her heart and soul and blood. But she wonders how she can find a place for herself here now. She says:

‘The world here is so cut off from reality. It’s been frozen in the past. People live as our ancestors did thousands of years ago. Though I love this country, I’m not sure how I’ll be able to adapt to it again. Perhaps it will have to accept my values, not the other way around.’

Even if it be gilded, a cage is still a cage, and Ava does not want to live her life trapped, in the shadow of men. She has tasted freedom in England and it has changed her irrevocably. Can she find a way to be her own woman – strong, independent and yes, adventurous – in this conservative society? Can she find love with a man who’ll see her as his equal?