Unrest in Egypt: Sewing the seeds for revolution

Unrest in Egypt: Sewing the seeds for revolution

Unrest in Egypt: Sewing the seeds for revolution

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

The novel depicts a time in Egyptian history when the aristocracy, the British and the international officer class were living the high life of frivolity and glamour. What better time in which to set a novel than this bygone era of romanticism and hedonism?

But a storm was brewing, and this fairy-tale age would soon be over, never to be recreated. Come 1952, a group of army officers would stage a coup d’état, ousting King Farouk and ushering in a profoundly new era of nationalism and anti-imperialism which would bring about wide-scale social, economic and political change.

In Song of the Nile, I felt it was important to convey the rumblings of this great change. I write:

Egypt itself was looking at a new era – uncertain though it was – with the proposal of the Labour government in England to finally withdraw British troops from the country, alongside the disintegration of the Wafd – the traditional national party – which had been in power for so long.

Egyptian politics was in turmoil, giving militant nationalism the chance to harness the general discontent of a rapidly growing working class.

Embodying this nationalism is the character of Camelia, Aida’s best friend. Camelia is a widow whose husband had strong political opinions, and he inspired her deeply. Over the course of the novel, she opens up privately to Aida about her political leanings. She is certainly vocal in her anti-monarchy sentiments:

‘Our king is too busy gallivanting around to pay attention to negotiations with the British, or to look at the social conditions of his own people… In fact, the people now loath him for his foolish excesses and empty gestures. Throwing gold coins at the poor during his royal visits won’t make them love him. If we don’t want the fellahin to revolt, then we must give them proper living conditions, not grinding poverty.’

She does not see Farouk as a righteous king, but a puppet of the British who doesn’t trust that Egypt is capable of self-rule, which is what Camelia wants for her beloved country:

‘Throughout the war, Egypt made an important contribution to the Allied effort. Now the British are in debt to us for the first time. We were hoping to be rewarded for our support by a British declaration of complete independence when the war ended. Instead, we have been sorely disappointed by their refusal to change the status of our country, despite all the best efforts of Prime Minister Sidqi. All the talk of independence was nothing more than a sham, so is it any surprise that the British have forfeited what little goodwill they had left? It’s no wonder there have been massive strikes and demonstrations, people dying.’

People dying – certainly, to be involved with the nationalists is a dangerous business. Since the February student-led general strike, 47 students have died in confrontations with the police.

One night she comes to Aida covertly and begs for her help: her friend has been shot. Once Aida has nursed him to a comfortable state, Camelia explains that despite the danger, she believes in the nationalists and their cause.

‘I have a duty towards my country… We need to liberate our country from imperialism and our impotent government. The system needs to be adjusted. This might take time and it will certainly claim lives, but it needs to be done for the good of Egypt and Egyptians.’

Camelia will not be swayed by Aida’s concerned warnings; she is committed to her path. But when are those who would shake up the political order left to proceed as they wish? Danger looms indeed for her.

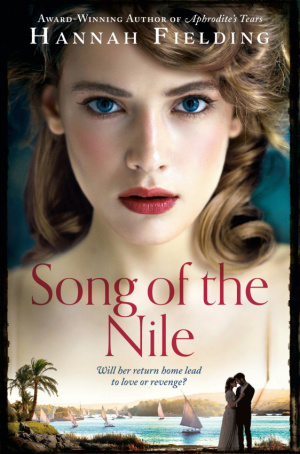

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Camelia represents so many Egyptians who strived for change in Egypt. The reasons went deeper than resistance to the monarchy, British rule and the disparity in the fortunes of the landowning elites and the mainly impoverished people; they came down to the importance of Egyptian identity. As Bruce K. Rutherford and Jeannie L. Sowers write in their book Modern Egypt:

The Egyptian nationalists of the early 20th century asserted that Egypt’s distinct identity lay primarily in its rich pharaonic history. They argued that Egyptians had been a single nation for millennia and that the greatness of the pharaonic era showed the enormous potential of a unified Egyptian people.

Over the years, notions of identity have shifted, so that ‘the struggle over Egyptian identity is closely tied to competing political visions for the country’. Thus the context of Song of the Nile is a deep-seated need for people to define Egypt based on both its very old, very important history and the potential for its future. No matter whether you agree with their politics and actions, Camelia, and so many like her, were revolutionaries, but also simply people who loved their country with great passion.

Photo credit: Stokkete/Shutterstock.com