Silent, mysterious, illimitable: The Egyptian desert

Silent, mysterious, illimitable: The Egyptian desert

Silent, mysterious, illimitable: The Egyptian desert

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Egypt is a country of deserts: more than 94 per cent of the land is desert territory. Thus the desert is at the core of Egyptian identity, history and culture.

In Song of the Nile, the desert is an ever-present backdrop in the landscapes. It is not dormant, still, simply a contrast to the blue waters of the Nile and the glorious colours of the sky. It is like its Sphinx: an eternal silent sentry and a fierce protector. Covetous too, for how many ancient monuments and tombs have been swallowed by the sands, buried deep in the desert’s embrace?

For Aida, the desert is a place of mystery, somewhat daunting for its vast expanses – as Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote in ‘Ozymandias’, ‘The lone and level sands stretch far away.’ There is a sense of danger associated with the sands too: here lurk thieves, and oases that are home to princes who would entrap a woman in their harems.

But Phares has a very different outlook – an affinity with the desert. I write:

Even as a child, when he was not yet allowed to go far into the desert unaccompanied, Phares had dreamed of its exquisite silence. He had replayed in his mind the songs of the Bedouins that he had heard one night when out riding with his father. And once he was old enough to realise his dream, he discovered that the desert of his imagination had been but a pallid reflection of its true glory. As a teenager he would ride out into it alone and one night he stumbled upon a Bedouin tribe who had welcomed him in, taught him how to ride bareback and allowed him to help rear one of their foals, which he named Zein el Sahara, Prince of the Desert. From then on, Phares had been equally at home in the wilderness of burning sands as he was in the bustling metropolis of Cairo.

He is keen to show Aida the majesty and tranquillity of this place, how its presence has power to soothe and balance a soul, how an Egyptian belongs in and to the desert. He takes her into the desert in the evening, to see the expanses anew. He tells her:

‘The desert is what you make of it, chérie. You dream it, you have hopes about it, embellish it, and one day you discover it and you don’t know what to think or say. It intimidates us into silence. You watch the sunset, you marvel at the subtlety of colours, and then you return to your inner self, to your thoughts. But the desert only makes sense if you take the time to stay in it. If not, it gives nothing. It remains a postcard, the image of a lacklustre memory.’

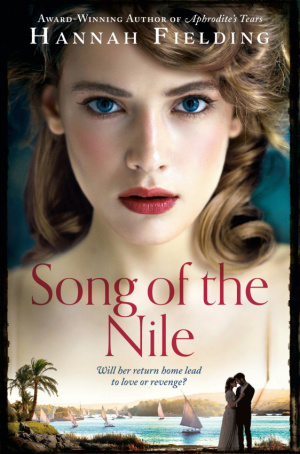

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Phares speaks of the desert as if it is a living, breathing entity. ‘I have known it in all moods,’ he says, ‘yet each time I ride, its sweeping spaces offer something new.’ This connection with nature, with the wild, he believes, is ‘a necessity for man’s spirit and as vital to our lives as bread and water’.

Later, Aida reflects on how she experiences the desert:

Aida sat on the balcony outside her room in a warm and sheltered corner, looking out across the rooftops and trees to the line of glinting gold which was the desert. She thought of Phares and how he had told her that he occasionally went out there, far into that vast emptiness, alone. She too loved the desert: she had tramped enough of it with her father, looking for buried tombs and undiscovered temples. Still, she had to admit that she loved it as a stranger, a visitor, an excavator. To her it was exotic, something wonderful to see, a place where she had camped with her father a few times, but which still held a lot of mystery. But to Phares, those sandy wastes were a part of his existence. That great family could have been descended from the Pharaohs themselves: the desert was in their blood.

Yet the desert is in her blood too, if only she will open her mind and heart.

In his wonderful book The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote:

I have always loved the desert. One sits down on a desert sand dune, sees nothing, hears nothing. Yet through the silence something throbs, and gleams… One runs the risk of weeping a little…

This is exactly how I feel when I stand in the desert of my homeland, attuned to the surroundings. There is not only a song of the Nile – there is a heartbeat in the desert. It is alive; it is vital.

Photo credit: Anton Petrus/Shutterstock.com.