‘Flying without wings’: the Arabian horse in Song of the Nile

‘Flying without wings’: the Arabian horse in Song of the Nile

‘Flying without wings’: the Arabian horse in Song of the Nile

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

These were the horses of the nomadic Bedouin people of the Egyptian deserts; these were the horses that drew the chariots of ancient Egyptian pharaohs.

These days, just about every horse has some Arabian heritage, but it is the pure-blooded Arabians that are most valuable. In the early 19th century, Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt established the first stud based on horses bred by the Bedouins, and the modern Egyptian Arabian is descended from that stock. So-called ‘Straight Egyptian Arabians’ are rare, with only a few thousand in existence worldwide, making up around 3 per cent of all Arabians, so they are especially valuable.

I love the Egyptian Arabian horse: spirited yet sensitive, strong and fast, majestic and so very beautiful; so of course I featured them in Song of the Nile. Aida attends a polo match at the Gezireh Sporting Club, and she rides out through the desert to the palace of Prince Shams Sakr El Din, where she and the other guests watch a tournament between the Prince’s equestrian guards and Bedouin nomads, an exhibition of perfect horsemanship.

But it is with Phares that Aida has her best experience of the Egyptian Arabian horse. When he takes her for a ride one evening, it’s an opportunity for him to share his knowledge and passion for Arabian horses. He rides one of his favourite stallions, Bourkan – Volcano, so named because when given free rein his galloping hooves sound like an erupting volcano. I write:

Aida watched as he mounted Bourkan, who did his best to get rid of his rider. Using his wits and horsemanship, Phares stuck on. Aida could see immediately that the stallion was not only swift but free-spirited, occasionally giving way to youthful exuberance, dancing sideways as they went. But trained to the nth degree, he finally became amenable to Phares’s touch on the rein, settling down to business, aware that a master was in the saddle. Phares recognised to a fraction the difference between high spirits and vice, and knew exactly how far he might indulge his Arab mount, and when he needed to bring Bourkan to heel without jerking the horse’s sensitive velvet mouth unnecessarily. It was wonderful to watch the two wills, that of the man and his beast, fighting for supremacy.

For Aida, Phares has chosen a calmer horse, a beautiful fawn-coloured mare called Bint El Nil, Daughter of the Nile. She’s a descendant of Baz, he explains, a Berber name from the desert-born legend ‘The Birth of a Stud’ in Tales from the Arabian Nights. This is the legend of Baz, as told by Phares:

‘In a tale whispered through the ages, it is rumoured the mare was born from the breath of the Creator. No animal on earth could improve upon her nature or form. It’s said that she was in foal and gave birth to a colt, and in time they were mated. For generations her descendants replicated her perfect beauty, intelligence, and agile strength. She was named Baz, and is the Eve of the Arabian horse breed. For thousands of years, the original shepherd’s descendants bred the pure stock of Baz. Her family grew and branched out, as did her caretaker’s, until the desert lands were renowned for both the nomadic Bedouin tribes and their unique hot-blooded horses.’

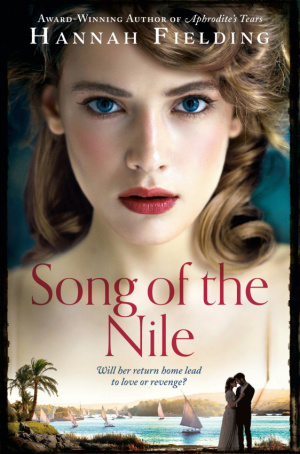

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

After a moonlit ride out to the Sphinx, Aida and Phares are cantering back across the hard sand when Aida’s saddle slips. Phares quickly catches her and pulls her onto his own horse. As Bint El Nil gallops back to the stable alone, Phares and Aida ride Bourkan, and Phares endeavours to educate Aida in the ways of the Bedouin. ‘They are much more attuned to nature than those in what we call the civilised world,’ he tells her. ‘I can assure you that on horseback you’ll see, feel and enjoy more in one mile than you would in a hundred sitting in a car.’

And indeed, she does see and feel. I write:

Phares now urged his horse into a canter. While the Arabian horse’s gait was fluid, moving smoothly under Phares’s command, Aida still had to adjust herself to its faster motion, aligning her back snugly against Phares’s hard chest as he instinctively held her tight against him. Together, their bodies moved rhythmically as one…

For a crazy instant, giving herself to the fresh breeze and the swift motion while he had spurred Bourkan on, something had tugged at Aida’s heartstrings… Held like this in Phares’s strong arms against his beating heart, upon a racing Arab galloping off into the desert, love, like a velvet fist, reached out and struck through her skin to her very heart and gripped her. All of a sudden, she realised what love and passion could be, coming alive as she had never done before.

It is as Helen Thompson said: ‘In riding a horse, we borrow freedom.’ Freedom to breathe, to think, to feel, to live… to love.