An epic love story or a marriage of convenience?

An epic love story or a marriage of convenience?

An epic love story or a marriage of convenience?

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

In my new book, Song of the Nile, Aida is under pressure to marry Phares. In many ways, they make a good match: he’s a family friend, a successful doctor and the owner of the neighbouring estate. Which means their marriage would see the amalgamation of their land into one very impressive estate run by… Phares. For this is 1940s Upper Egypt, where men are very much in charge.*

By Egyptian standards, it is ‘a marriage made in heaven’. There is a long tradition of arranged marriages, and Aida discovers that some can work out well. Her best friend, Camelia, married a much older man and was devastated when he died. Phares explains to Aida:

‘For her, Mounir ticked all the right boxes. She made a rational decision, knowing the main ingredients were there to make the marriage successful. I think it was one of your English Restoration rakes, the Duke of Buckingham, who said that “all true love is founded on esteem”. Mounir was a great man. He was many years older than my sister but he was well-established, wise, respected in the community and kind. There was mutual understanding, respect and admiration between them. The rest came later.’

For Phares, this is proof that it isn’t absolutely necessary to be in love to make a marriage work. But Aida struggles with this idea. Epic love stories are part of the histories of both their families – and in all of the stories the couples chose love over tradition.

Aida’s parents met when her mother, Eleanor, and her family were passing through Egypt on their way back from India to England. At a drinks party at the British Embassy in Cairo she met Ayoub, a well-known archaeologist. It was love at first sight and the two eloped and married very shortly afterwards. The ensuing scandal caused Ayoub to be disowned by the rest of his family and wide circle of friends, and Eleanor to be cut off from her own.

Phares’s grandparents, Sélim and Gamila, were very much in love and officially engaged, but they had to respect the custom which dictated that they should not see each other until they were married, except on special occasions when both families were gathered. This was unbearable, and so they would meet in secret, until finally, tired of the gossiping of their neighbours, they decided to give the people of Luxor something to talk about. One day, Sélim took Gamila on horseback through the town to the market.

Both these stories had happy endings: in time, society came to accept the mixed marriage of Eleanor and Ayoub, and people came to accept Sélim and Gamila riding together. But rule-breaking did not always go unpunished. When Phares’s great-grandfather, Boutros, tried to elope with a Bedouin woman, Gawahir, they were both murdered by Gawahir’s brother, Seif.

Still, Aida cannot help but be inspired by the romance in these family histories. Her ancestors and Phares’s were so committed to their love, prepared to be together despite the traditions of the time and the judgements of others. Is it so wrong to yearn for such love for herself? To wish for romance and passion, rather than just ‘mutual understanding, respect and admiration’? Is Phares right that it isn’t necessary to be in love to make a marriage work? Will love naturally follow, as he seems to believe, or must it be there from the outset?

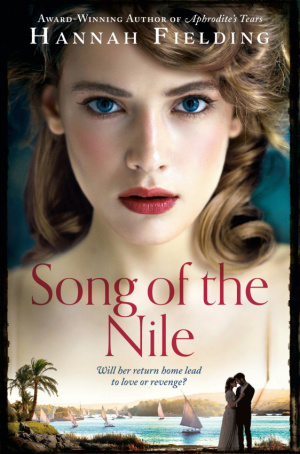

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

The truth, Aida will soon discover, is that from her side it would not be a loveless marriage; she feels a great deal for Phares. But how does he feel? Would this be nothing more than a marriage of convenience for him, or could he come to love her too?

Ultimately, will they make history together for their families; will their grandchildren tell the story of their epic romance?

* It may interest you to know that in Ancient Egypt women had the same legal rights as men in their class, which meant that women could own property and manage their land as they wished without input from a man. (This didn’t apply to royal women, however, who had very few rights and were often locked away in a harem.)