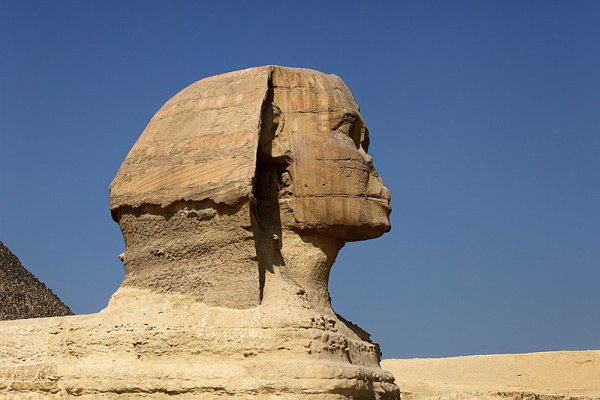

‘Eternal secrecy’: The Sphinx of Giza

‘Eternal secrecy’: The Sphinx of Giza

‘Eternal secrecy’: The Sphinx of Giza

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

Carved from the limestone bedrock at the Giza pyramid complex, the Great Sphinx is an immense 73 metres long and 20 metres high, and it’s believed to date back to the reign of King Khafre (c. 2558–2532 BC).

The sphinx is a mythical creature with the body of a lion, the wings of an eagle and the head of a human, a falcon or a cat. The Great Sphinx has the body of a lion and the head of a human, and many believe it represents Khafre, but as Aida points out in my novel Song of the Nile, the ancient Greeks believed sphinxes were female:

‘Shall we go down to the Sphinx?’ asked Phares.

‘Yes, it’s never so impressive than by moonlight,’ Aida replied keenly.

‘I’ve seen him at various times of the day and at each hour I find he has a different expression but I think it’s by moonlight that I like him the best.’

‘You automatically say he. Is the Sphinx a man? Wasn’t the Greek Sphinx of Thebes a woman?’

‘Man or woman, it’s the most extraordinary piece of sculpture ever wrought by human hands, even if its sex is lost in that pitiless, stony glare.’

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

The Great Sphinx has an undeniable presence. Here is how Aida feels as she approaches it in the moonlight:

Cantering now, they descended to the deserted hollow wherein lay the Sphinx. The huge sculpture, carved out of the solid rock of the plateau, was half buried in the sands. The moon softened the gaze of its sightless eyes and threw the sharp shadow of its mighty back on the face of the desert. In this soul-stirring atmosphere it wore the mystic look for which it was renowned, one which spoke of eternal secrecy. At a standstill on their horses, Aida and Phares did not speak but stared up at the mighty sandstone figure so disdainful of man, marvelling at the leviathan’s length. It was almost terrifying in this vast solitude. Silent, menacing, a crouching half man, half lion lying at the edge of the desert, it gazed through human eyes towards the dawn.

‘It makes you feel like an ant,’ Aida whispered to Phares.

The Great Sphinx stands alone, but other sphinxes from ancient times have been discovered, like the granite Sphinx of Hatshepsut, depicting the female pharaoh Hatshepsut, and the alabaster Sphinx of Memphis. In Song of the Nile, Aida and Phares pass along an avenue of sphinxes in the Karnak Temple, and Aida passes a pair of stone sphinxes from the Temple of Serapis at Memphis as she enters the Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo. All these sphinxes had the role of guardian, protector.

The Great Sphinx’s symbolism grew in the reign of Amenhotep II (1427–1401 BC), when it came to represent ‘Ra-Horakhty’, the sun god Ra combined with Horus, the god of kingship. By this time the immense statue had been buried to its shoulders by the desert, the Giza pyramid complex having been abandoned. Apparently, Tuthmosis IV, son of Amenhotep, fell asleep in the shadow of the Sphinx, and it spoke to him in his dreams, saying:

‘Observe me, my son Tuthmosis. I am your father, Ra-Horakhty. I shall give you kingship upon earth and you shall wear its red crown and its white crown. But see how I am in pain and my body in ruins, for the sand of the desert now presses down on me. I know you are my son and protector so approach me, I am with you, I am your guide.’ (Translation from The Story of Egypt by Joann Fletcher)

Tuthmosis recorded his dream in the ‘Dream Stele’, erected between the paws of the Sphinx, and saw to it that the Sphinx was uncovered (in what may well have been the earliest archaeological excavation). It was later reclaimed by the desert once more, and was most recently uncovered in 1925.

Perhaps inspired by Tuthmosis’s experience, in Song of the Nile Phares explains to Aida that he too slept by the Sphinx one night. ‘One feels very privileged to lie under a wondrous sky, gazing at the majestic calm of the Sphinx’s face,’ he tells her. Then he adds: ‘We must do it together some time.’

Would you sleep by this ancient sentry? I wonder what dream the Sphinx would give you.