Tomb robbing in Ancient Egypt

Tomb robbing in Ancient Egypt

Tomb robbing in Ancient Egypt

-

Hannah

-

Hannah

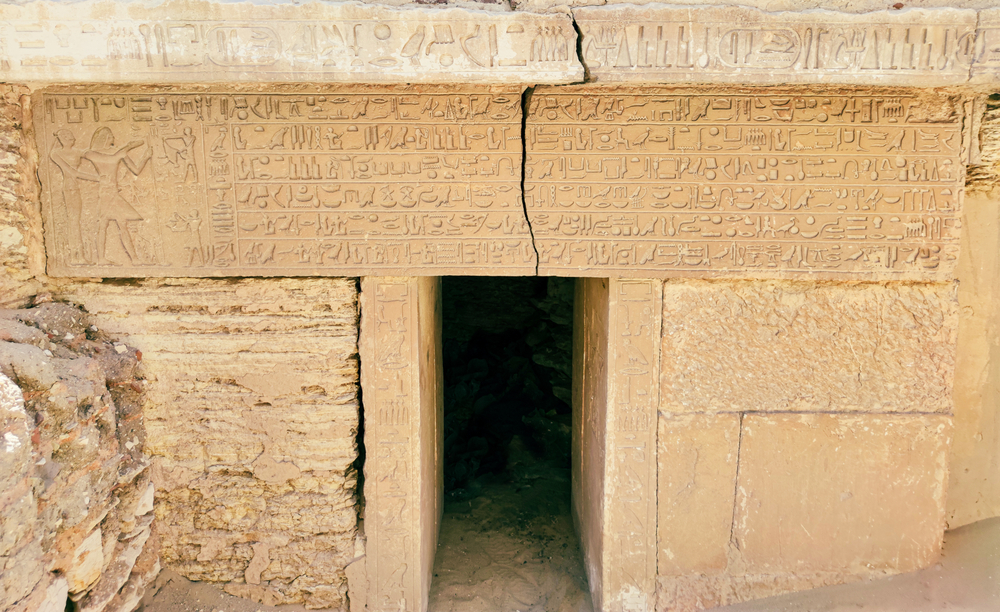

Entrance to the looted tomb of Djoser

The Ancient Egyptians built great tombs for their kings and nobles to honour their memories, but most importantly to protect their mummies and their precious belongings. Yet every tomb that has been discovered has been found looted. Though warnings were inscribed in tombs and people were frightened of retribution by the angry spirits of the kings, this was not enough to deter treasure hunters.

The Great Pyramid was built during the Old Kingdom, and was carefully constructed to protect the burial chamber. Yet the sarcophagus in the burial chamber was found to contain bull bones, the mummy having been stolen. The Step Pyramid at Djoser was similarly robbed, even though the passages leading to the tomb were filled with rubble.

Come the Middle Kingdom, tomb raiding had become a big problem. Families would visit often to check a tomb was sealed, and they would even hold off on burials for years to avoid opening the tomb too often, keeping mummies in their homes.

Pharaoh Amenemhat I was so concerned about the prospect of his tomb being raided that he ordered the construction of a new burial site at Deir el-Medina, located in the desert and difficult to access. He also came up with a cunning plan: build a pyramid for himself that had a maze of tunnels inside, and hidden rooms, and secret doors. The men who built the pyramid had to enter each day in a blindfold, so that only the pharaoh knew the exact layout. Even then, his tomb was robbed, and the robbers were so unimpressed with the hard work they’d had to put in to find the tomb, they burned Amenemhat’s mummy.

New Kingdom tombs for pharaohs were situated underground, to make robbery more difficult and to enable entrances to be hidden. In the Valley of the Kings, Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered, and it was found that it had been robbed twice (it was saved from further looting simply by the fact it was buried accidently when workers built the nearby tomb of Ramesses VI). At Thebes, meanwhile, tomb robbers completely desecrated mummies, slashing them open in search of treasures within the body cavities. The Papyrus Salt even indicates a culprit from the time: Paneb was accused (and most likely guilty) of stealing many items from the tomb of Sety II.

It would be all too easy to think tomb robbing only occurred way back in the past, perpetrated by poor people who would use treasure to barter and rich people seeking shiny prizes for their tombs. But the growth of Egyptology in the 19th century saw many tombs discovered and artefacts taken. This problem has persisted through the 20th century, as I explore in Song of the Nile. Here is a conversation between Aida and a historian and lecturer at the University of Cairo.

‘These antique dealers are getting their hands on stolen antiquities all the time,’ said Aida. ‘While foreign Egyptologists are here selling these artefacts for thousands of pounds to their foreign buyers, there will always be looters. They are simply supplying a market.’

‘Yes, yes, that is true, young lady,’ said Geratly… ‘But one must understand, these objects have always been taken and sold on.’ He gave a huff of amusement. ‘Even the Egyptian Museum is selling genuine artefacts in its gift shop. And after all, who owns the past? Can we claim ancient artefacts as our cultural property? We ourselves are almost an entirely different culture to our Ancient Egyptian ancestors, are we not? I have written a paper on just such a subject.’

Aida raised an eyebrow. ‘There are many Egyptians who would fiercely disagree with you, Adly Bey. My father certainly would have been hotly opposed to that line of thought. He argued passionately for preserving our antiquities here in Egypt.’

To think of all the historic treasures that Egypt has lost… clearly, we must preserve as many as we can.

Song of the Nile: available to buy now

Photo credit: diy13/Shutterstock.com.